One of the more important tools in my computational toolbox is linear programming. It's a great way to solve a lot of otherwise difficult problems in a straightforward, nearly black-box manner. I've discovered that a lot of programmers aren't too familiar with it, so I'm writing this tutorial that explains how to use it in practical purposes.

The problem

Specifically, I'll discuss AWS capacity plannning. On AWS, you have two types of servers.

The first is an on-demand instance. You can spin these servers up or down whenever you want. An extra large server costs you $0.64/hour if you rent it on-demand.

The second type of server is a reserved instance. To use a reserved instance, you must pay a large fixed cost. After that, to use the server you pay a much lower hourly rate. The specific costs:

- Heavy utilization - $1560/year $0.128/hour

- Medium utilization - $1280/year, $0.192/hour

- Light utilization - $552/year, $0.312/hour

I'll demonstrate shortly (with a few lines of Haskell) how to use linear programming to provide sufficient capacity while minimizing your costs.

Introduction

Linear programming is the science of solving a deceptively simple math problem:

find argmax f(x)

subject to constraint: M*x >= v

Here, x is a finite dimensional vector, in computational terms, an array with N elements in it.

f(x) is a linear function of type: R^N -> R (vectors of N real numbers to a single real number) with the property that f(a*x+y)=a*f(x)+f(y). Here, a is a scalar, and y is also a vector. f(x) is typically called the objective function.

The constraint takes the form M*x >= v, where M is a matrix, and v is a vector. Inequality is interpreted pointwise. A simple example:

find argmax 1.5*x+y

subject to:

x >= 0

y >= 0

-1*x + -2*y >= 4

The constraints demand that the solution (x, y) lives in a bounded set, specifically the triangle with vertices (0,0), (4,0) and (0,2). And the goal is to make 1.5*x+y as big as possible.

So where can the solution lie?

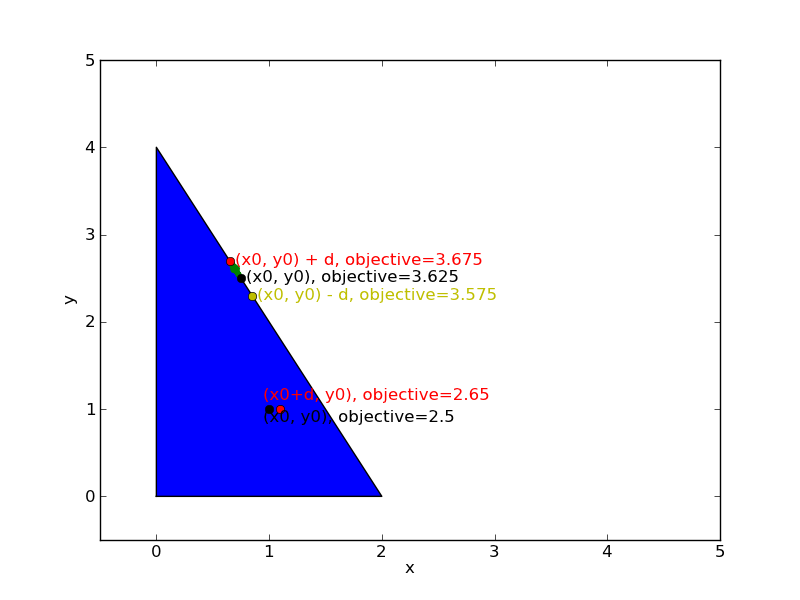

The first fact to observe is that it can't lie on the interior of the triangle. It must be on one of the edges. To see why this is so, imagine the maximum were at some point(x0, y0) inside the triangle but not on the edge. In that case, I can find a very small value d for which (x0+d, y0) is still inside the triangle - specifically, I just pick d equal to half the distance to the edge. If I compute f(x0+d,y0) = 1.5*x0+1.5*d+y0, then this value is bigger than f(x0,y)=1.5*x0+y0. This means that (x0, y0) was not really the maximum.

I can make similar arguments about the edges. Suppose p is a point on the edge of triangle (but not the corner), and suppose d is a vector pointing along the edge. By the linearity of the objective function, f(p+d)=f(p)+f(d). If f(d) > 0, then I can increase the objective function by moving in the direction of d, otherwise I can increase it by moving in the direction of -d. This means the maximum can't be on the edge either, except in the special case that f(d)=0.

So since the maximum of the objective function doesn't live inside the triangle or on the side, we find it must like at one of the corners of the triangle.

This observation gives rise to the simplex algorithm. The simplex algorithm, as oversimplified by myself, consists of the following:

- Start at at a corner

- Compute the set of edges adjacent to this corner for which moving away from the corner along that edge increases

f(x). - Pick one of these edges, and follow it until you reach another corner.

- Repeat until you can't find any directions to move which increase

f(x). - Declare victory.

In practice, you need to be a lot more careful than this. But in principle, this is the core of the simplex algorithm.

How it's used

To begin, make sure you have the GLPK installed. On an ubuntu system with cabal installed, run:

$ sudo aptitude install glpk glpk-dev

$ cabal install glpk-hs

Now let's represent our problem in Haskell.

For simplicity, suppose we have 3 typical 8-hour load periods - midnight-8AM, 8AM-4PM, and 4PM-midnight. During these periods, we expect various load patterns. For example, we might expect:

loadPattern = Map.fromList [ ("night", 5), ("morning", 25), ("evening", 100) ]

As I mentioned in the intro, we have the option of using Amazon on-demand instances or various types of reserved instances. Amazon's pricing is described here, so all we need to do is translate this to code.

First we need some basic imports:

module Main (

main

) where

import Data.LinearProgram

import Control.Monad.LPMonad

import Data.LinearProgram.GLPK

import Control.Monad.State

import qualified Data.Map as Map

Then we define our costs, for on-demand instances:

onDemandHourlyCost = 0.64

Then, reserved instances:

reservationFixedCosts = [("light", 552.0), ("medium", 1280.0), ("heavy", 1560.0)]

reservationVariableCosts = [("light", 0.312), ("medium", 0.192), ("heavy", 0.128)]

reservationTypes = map (\(x,y) -> x) reservationFixedCosts

Now let's write our objective function, given a load pattern. Although we are trying to minimize rather than maximize it, everything I said in the introduction applies.

We will do this as follows. We will first construct a list of tuples, of the form [(3, "x"), (2, "y")]. We then pass this to the function linCombination

from glpk-hs, which translates this into a form glpk can read. I.e., linCombination [(3, "x"), (2, "y")] is interpreted by glpk to mean 3x+2y.

dailyCost :: Map.Map [Char] Double -> LinFunc [Char] Double

dailyCost loadPattern = let

periods = Map.keys loadPattern

reservationFixedCostsObj = [ ( cost / 365.0, "reservation_" ++ kind)

| (kind, cost) <- reservationFixedCosts ] -- cost of reserving an instance

reservationVariableCostsObj = [ (cost*8, "reserved_" ++ kind ++ "_" ++ period)

| (kind, cost) <- reservationVariableCosts,

period <- periods ]

-- cost of *running* the reserved instance

onDemandVariableCostsObj = [ (onDemandHourlyCost*8, "onDemand_" ++ p) | p <- periods ]

-- cost of running on-demand instances

in

linCombination (reservationFixedCostsObj ++ reservationVariableCostsObj ++ onDemandVariableCostsObj)

Now we need to actually represent the problem to glpk. We do this using our constraints.

The first constraint is that we actually need to meet our capacity requirements:

capacityConstraints loadPattern = [ (linCombination (

[ (1.0, "onDemand_" ++ period) ]

++ [(1.0, "reserved_" ++ k ++ "_" ++ period) | k <- reservationTypes]

),

load)

| (period, load) <- (Map.assocs loadPattern)]

This set of constraints means that in any period, the number of on-demand instances running plus the number of reserved instances running must be high enough to meet capacity in that period. I.e.:

(# on-demand) + (# light reserved) + (# medium reserved) + (# heavy reserved) >= desired capacity

The second constraint tells GLPK that in order to use a reserved instance, we need to reserve it first.

reservationConstraints loadPattern = [ linCombination [ (1.0, "reservation_" ++ k),

(-1.0, "reserved_" ++ k ++ "_" ++ p) ], 0.0 |

p <- (Map.keys loadPattern),

k <- reservationTypes ]

In traditional math terminology, this is just the constraint that:

(# heavy instances reserved) - (# heavy reserved instances running at night) >= 0

Equivalently:

(# heavy instances reserved) >= (# heavy reserved instances running at night)

(And similarly for other periods, and for medium and light instances.)

The final set of constraints is that all these quantities must be positive. We just create a list of variables, and then use the glpk function varGeq on each of these variables:

allVariables loadPattern = ["onDemand_" ++ p | p <- periods] ++

["reserved_" ++ k ++ "_" ++ p | p <- periods, k <- reservationTypes] ++

["reservation_" ++ k | k <- reservationTypes]

where periods = Map.keys loadPattern

Now we actually call glpk:

lp :: Map.Map [Char] Double -> LP String Double

lp loadPattern = execLPM $ do

setDirection Min

Tell glpk we want to minimize, rather than maximize.

setObjective (dailyCost loadPattern)

Tell glpk what we want to minimize.

mapM (\(func, val) -> func `geqTo` val) (reservationConstraints loadPattern)

mapM (\(func, val) -> func `geqTo` val) (capacityConstraints loadPattern)

Tell glpk about our first and second set of constraints.

mapM (\var -> varGeq var 0.0) (allVariables loadPattern)

Tell glpk that all variables need to be positive.

mapM (\var -> setVarKind var IntVar) (allVariables loadPattern)

Lastly, we'll tell glpk to make each variable an Integer (since we can't reserve fractional instances).

Finally, a little function to print the results:

printLPSolution loadPattern = do

x <- glpSolveVars mipDefaults (lp loadPattern)

putStrLn (show (allVariables loadPattern))

case x of (Success, Just (obj, vars)) -> do

putStrLn "Success!"

putStrLn ("Cost: " ++ (show obj))

putStrLn ("Variables: " ++ (show vars))

(failure, result) -> putStrLn ("Failure: " ++ (show failure))

And we run.

main :: IO ()

main = do

printLPSolution (Map.fromList [ ("night", 12.2), ("morning", 25.1), ("evening", 53.5) ])

This applies to the particular case that we need 12 servers at night, 25 in the morning, and 53 in the evening. The result:

Success!

Cost: 289.9164931506849

Variables: fromList [("onDemand_evening",0.0),

("onDemand_morning",0.0),

("onDemand_night",0.0),

("reservation_heavy",26.0),

("reservation_light",28.0),

("reservation_medium",0.0),

("reserved_heavy_evening",26.0),

("reserved_heavy_morning",26.0),

("reserved_heavy_night",13.0),

("reserved_light_evening",28.0),

("reserved_light_morning",0.0),

("reserved_light_night",0.0),

("reserved_medium_evening",0.0),

("reserved_medium_morning",0.0),

("reserved_medium_night",0.0)]

(Output formatted slightly for the web.)

So now we know what we need to do. We make 26 heavy reservations and 28 light ones. At night we run 13 heavy reserved instances. In the morning we run 26 heavy reserved instances. In the evening, we run 26 heavy reserved instances and 28 light reserved instances.

As this post shows, linear programming is fairly straightforward to use. The original code only contains about 30 lines of code, ignoring the printLPSolution function (this blog post contains a few more lines of code, since I reformatted a bit for the web). And once you learn it, it's a great tool to have in your toolbox. A surprisingly large number of problems can be solved using linear programming, and calling glpk is virtually always easier than writing your own code to solve the problem.

P.S. This blog post is generated from literate Haskell - it's a great way to write code. If you go read the source code for this program, you'll discover it's the blog post itself.