Basic Income is a popular policy floating around the internet lately. The idea consists of declaring that the government will pay each living adult a fixed amount of money every month - an amount comparable to a minimum wage job. This policy would then replace all current welfare programs - welfare, unemployment, SNAP, WIC, housing vouchers, etc, would all be terminated. There are no qualifications beyond being an adult citizen to receiving a Basic Income.

An alternate proposal, though less popular nowadays, is a Basic Job. The Basic Job is another way of providing income support to anyone who needs it. The idea consists of a basic income, but with a single qualification - you need to do basic work for the basic income. In short, the government will give a low skill job to anyone who cannot find one elsewhere. This is basically a modern variation on FDR's Civilian Conservation Corp.

Like most political arguments, the discussion of a Basic Income borders on innumeracy. So I'm going to take the opportunity to launch into a far more interesting mathematical tangent, and illustrate how to use Monte Carlo simulation to understand uncertainty and make business/policy decisions. I promise that this post will be far more interesting to python geeks than to policy wonks. I'm just picking Basic Income as a topic to discuss since it showed up on hacker news yesterday and it's a topic where I see basically no numbers whatsoever.

Mathematical Modelling

The basis of any informed discussion is a mathematical model. The best way to think of a mathematical model is a way to force everyone to clearly enumerate all assumptions being made, and to accept all logical reasoning that follows from those assumptions. Given a model, everyone involved in a discussion can agree that either the conclusions of the model are correct, or one of the assumptions going into the model must be false. This is very important when disagreement is reached - disagreement in the conclusions implies disagreement with some assumption, so it makes sense to figure out which assumption is the cause of disagreement.

It's also important not to be blinded by a model. The involvement of numbers does not make an argument empirically correct - it simply makes it more understandable and less likely to be logically flawed.

Monte Carlo Simulation

Monte Carlo Simulation is a way of studying probability distributions with sampling. The basic idea is that if you draw many samples from a distribution and then make a histogram, the histogram will be shaped a lot like the original distribution. In code, I can either plot a probability distribution:

from scipy.stats import norm

x = arange(-4,4,0.01)

plot(x, norm().pdf(x))

Or mostly equivalently, I can draw samples from the normal distribution and plot a histogram of them:

from numpy.random import normal

s = normal(size=(1024*32,))

hist(s, bins=50)

As we will see shortly, this property is very handy because it is usually a lot easier (from a programming perspective) to draw samples from a probability distribution than it is to explicitly model it.

Modelling Policy Choices

To study Basic Income (BI) and Basic Job (BJ), I'm going to focus on one specific aspect of it - a Cost/Benefit analysis studying the effects on the government budget, and the value of the work produced by people benefitting from the program. There are other aspects to consider, but I'm more interested in Monte Carlo than in politics, so I'm going to ignore those for the time being. However, I will build up a moderately complicated model of the effect of BI and BJ on the budget simply to illustrate how Monte Carlo sampling short circuits a lot of math.

Basic Facts and Assumptions

To begin with, our first fact:

num_adults = 227e6

This is correct as of the 2010 Census.

I'll also make our first policy choice. I'll assume that both the BI and BJ pay a quantity of money equal to working a full time minimum wage job for 40 hours/week, 50 weeks/year:

basic_income = 7.25*40*50

This works out to be $14480.

Another useful number is the size of the labor force, which was (as of Dec 2010):

labor_force = 154e6

A final useful number is the disabled population, aged 16 and over, which was:

disabled_adults = 21e6

One last useful number is the total size of wealth transfers in America. Wealth transfers comprise the bulk of government spending in the US. So to approximate the size of the programs that either a Basic Income or Basic Job could replace, I'll compute total government spending minus the cost of education, defense, protection, transportation and interest (again, all from 2010). This works out to be:

wealth_transfers = 3369e9

I'm not putting in much effort to evaluate the cost of wealth_transfers more accurately simply because it won't affect things much - it's just the effect of current policy for comparison.

Basic Income - costs and benefits

To determine the cost of Basic Income, we'll write a Python function. There will be a number of components. First is the direct cost:

direct_cost = num_adults * basic_income

The second is the administrative costs. We don't know what this is - all we can do is make some guesses. The administrative costs involve paperwork, mailing checks/direct deposit, verifying citizenship/adult status, and the like. It seems reasonable to me that this cost might be as low as $0, or as high as $500 (per person). I'll model this with a normal distribution of mean 250 and sigma of 75:

from scipy.stats import *

administrative_cost_per_person = norm(250,75)

If you disagree with these numbers or this distribution, there is no need for you to stop reading. Just download the code and change the numbers. Your change in these assumptions might completely invalidate my conclusions, or they might not matter at all. The best way to find out is to actually run the model.

An additional cost is the incentive or disincentive for engaging in productive work created by the Basic Income. On the one hand, the BI creates disincentives for recipients to engage in productive labor. If you are happy earning direct_cost each year, why bother putting down Call of Duty and getting a boring job? On the other hand, the BI removes certain disincentives for labor created by means-tested welfare schemes. The marginal income from labor under a BI is precisely (1 - tax_rate) * income, rather than (1 - tax_rate - lost_benefits) * income. As a result, it is unclear whether BI will cause the labor supply to increase or decrease.

My inclination is that it is more likely to reduce labor than increase it. So I'll assume that the number of non-working adults will increase by up to 10%, or decrease by up to 5%, and I'll model this with a uniform probability distribution:

non_worker_multiplier = uniform(-0.05, 0.15)

We also need to estimate the value of these worker's labor. I'll assume these are primarily workers with marginal productivity in the same neighborhood as the minimum wage, thus making it difficult for them to find highly productive employment. (I.e., a Basic Income of $14480 will not induce a banker earning $250k/year to stop working.) I'll model this with a normal distribution centered near $10/hour:

marginal_worker_hourly_productivity = norm(10,1)

Thus, the cost or benefit of the labor disincentive is:

-1 * (num_adults-labor_force-disabled_adults) * non_worker_multiplier.rvs() * (40*52*marginal_worker_hourly_productivity.rvs())

Note that the method .rvs() of a scipy probability distribution simply draws a sample from the distribution.

Finally, I'll model the JK Rowling effect - the propensity for otherwise unemployed individuals to create great works. (I describe it this way since JK Rowling wrote the first Harry Potter novel while being supported by the UK welfare system.) This clearly doesn't happen often - JK Rowling is quite an uncommon story. I'll model it as a 1 in 10 million situation, creating $1 billion worth of value.

def jk_rowling(num_non_workers):

num_of_jk_rowlings = binom(num_non_workers, 1e-7).rvs()

return num_of_jk_rowlings * 1e9

From this, we can compute the total cost/benefit of the basic income:

def basic_income_cost_benefit():

direct_costs = num_adults * basic_income

administrative_costs = num_adults * administrative_cost_per_person.rvs()

labor_effect_costs_benefit = -1 * ((num_adults-labor_force-disabled_adults) *

non_worker_multiplier.rvs() *

(40*52*marginal_worker_hourly_productivity.rvs())

)

return direct_costs +

administrative_costs +

labor_effect_costs_benefit +

jk_rowling()

Basic Job - costs and benefits

I'll assume the Basic Job is similar to the Basic Income. The amount of money provided will be the same - $14480 to every person working a basic job, and the same amount to every disabled person. But the big difference between these proposals is that non-disabled people must work for the money. The job will not necessarily be a productive one - we can take FDR's Civilian Conservation Corp as a model. People might be required to plant trees, pick up litter and build paths in national parks, and similar things. Not useless activities, but activities worth less than $7.25/hour.

There will be two types of administrative costs - one for the disabled and one for workers. I'll assume the disabled cost is double the administrative cost of the Basic Income, due to the need to verify disability:

administrative_cost_per_disabled_person = norm(500,150)

I'll assume the administrative cost per basic worker is much higher, since there will be supervisory work and supplies needed for basic jobs:

administrative_cost_per_worker = norm(5000, 1500)

Estimating the number of workers is trickier. The incentives for dropping out of the labor force are clearly less than those for a Basic Income. With a Basic Income, you can earn $14480 by choosing not to work. With a Basic Job, you can't - your choices are a Basic Job for $14480 or possibly a McJob for marginally more (say $15000). I'll model this by assuming the number of non workers will increase by up to 5%, or decrease by up to 20%:

non_worker_multiplier = uniform(-0.20, 0.25)

Here, "non_worker" actually refers to workers outside the basic job.

Additionally, the workers will produce something of value. The value is likely to be less than their wage, since if their marginal productivity was greater than $7.25, they would choose a job in the private sector paying that amount. But it could easily be greater than $0. I'll model this with a uniform distribution:

basic_job_hourly_productivity = uniform(0.0, 7.25)

Net result is that we come up with the following computation for the Basic Job cost/benefit:

def basic_job_cost_benefit():

administrative_cost_per_disabled_person = norm(500,150).rvs()

administrative_cost_per_worker = norm(5000, 1500).rvs()

non_worker_multiplier = uniform(-0.20, 0.25).rvs()

basic_job_hourly_productivity = uniform(0.0, 7.25).rvs()

disabled_cost = disabled_adults * (basic_income + administrative_cost_per_disabled_person)

num_basic_workers = ((num_adults - disabled_adults - labor_force) *

(1+non_worker_multiplier)

)

basic_worker_cost_benefit = num_basic_workers * (

basic_income +

administrative_cost_per_worker -

40*50*basic_job_hourly_productivity

)

return disabled_cost + basic_worker_cost_benefit

Monte Carlo time!

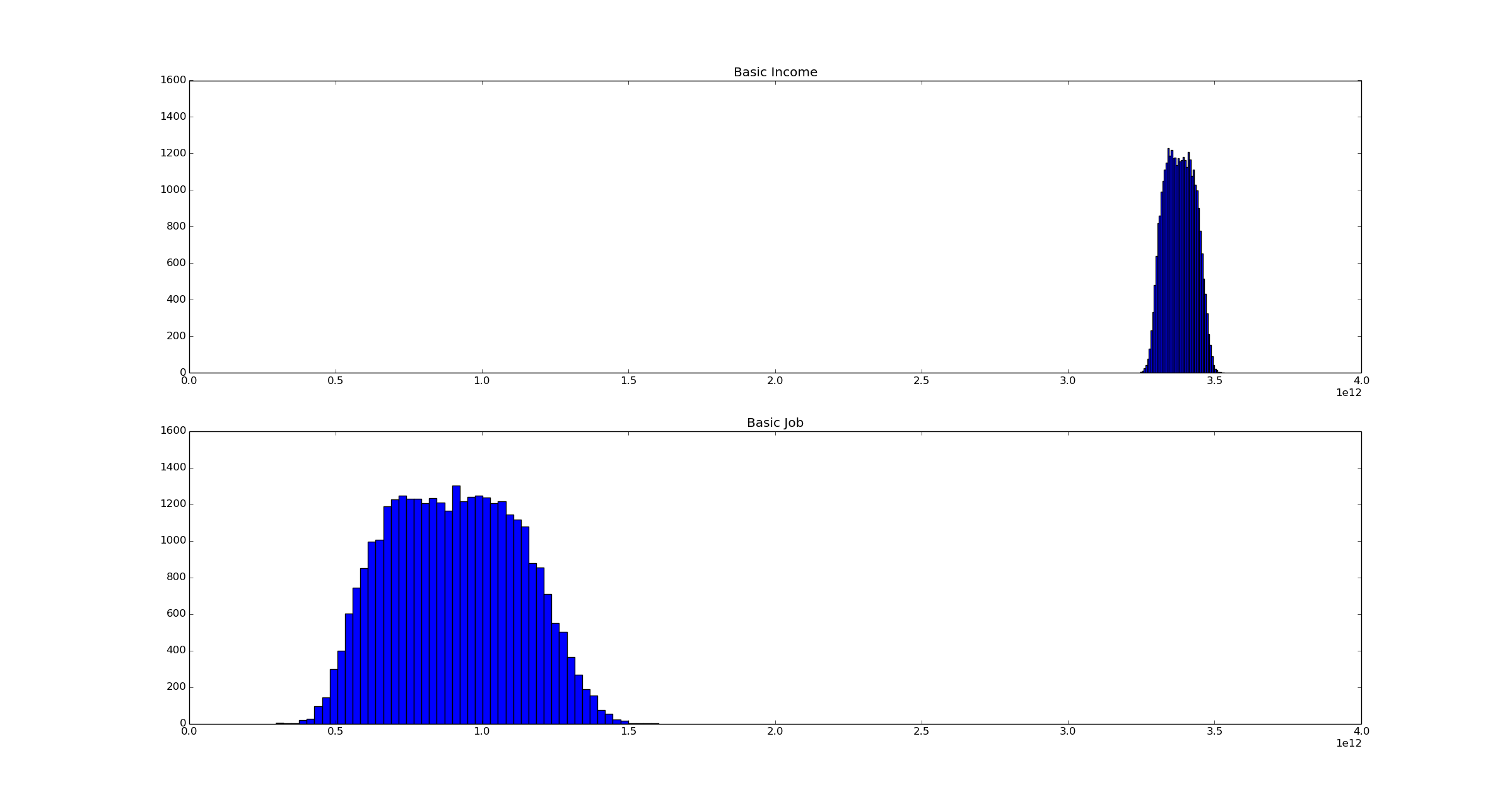

Both the functions basic_income_cost_benefit() and basic_job_cost_benefit() are nondeterministic. The nondeterminism represents our uncertainty. Their purpose is not to provide an exact number, but to give us a general picture of what might happen under each proposal. So to figure this out, we will call each function many times and make a histogram of each result:

N = 1024*12

bi = zeros(shape=(N,), dtype=float)

bj = zeros(shape=(N,), dtype=float)

for k in range(N):

bi[k] = basic_income_cost_benefit()

bj[k] = basic_job_cost_benefit()

subplot(211)

width = 4e12

height=50*N/1024

title("Basic Income")

hist(bi, bins=50)

axis([0,width,0,height])

subplot(212)

title("Basic Job")

hist(bj, bins=50)

axis([0,width,0,height])

show()

The results are displayed below:

Full source code is available on github.

According to this calculation, the cost/benefit almost certainly comes out in favor of a Basic Job. The Basic Job is likely to have costs - benefits of approximately $1 trillion (+/- $500 million), whereas the Basic Income is likely to have costs - benefits of approximately $3.25-3.5 trillion. By computing (bi.min(), bi.max()) and (bj.min(), bj.max()), we discover that out of 32,768 samples, the lowest cost/benefit of the Basic Income was $3.23 trillion, while the highest cost/benefit of the Basic Job was $1.55 trillion. (The lowest cost of the BJ was $328 billion.)

So according to this analysis and subject to the assumptions I've made, the Basic Job is a vastly better policy proposal than Basic Income.

How to Disagree: Write Some Code

This is a common theme in my writing. If you are reading my blog you are likely to be a coder. So shut the fuck up and write some fucking code. (Of course, once the code is written, please post it in the comments or on github.)

I've laid out my reasonining in clear, straightforward, and executable form. Here it is again. My conclusions are simply the logical result of my assumptions plus basic math - if I'm wrong, either Python is computing the wrong answer, I got really unlucky in all 32,768 simulation runs, or you one of my assumptions is wrong.

My assumption being wrong is the most likely possibility. Luckily, this is a problem that is solvable via code.

For example, maybe I'm overestimating the work disincentive for Basic Income and grossly underestimating the administrative overhead of the Basic Job. Lets assume both of these are true. Then what?

- non_worker_multiplier = uniform(-0.05, 0.15)

+ non_worker_multiplier = uniform(-0.10, 0.25)

- administrative_cost_per_worker = norm(5000, 1500)

+ administrative_cost_per_worker = norm(7500, 2000)

It turns out that even if you believe I made these mistakes, my conclusions are still likely to be correct. Basic Income is likely to be a bit cheaper, Basic Job a little more expensive, but overall the Basic Job is still far more likely to be the better option. On the other hand, maybe a clever reader can come up with some assumptions or analysis that make Basic Income a better possibility. I'd love to see what sort of assumptions lead to that conclusion.

The universe is made out of math. For us to understand the universe, we need to start using more math rather than simply words. Monte Carlo simulation is a great tool towards that end - it allows us to quantify and understand the uncertainty in our models. As demonstrated by the example here, there is a lot of uncertainty the cost of a Basic Job - it could be anywhere from $500B to $1500B depending on the true value of the parameters involved. That's a wide range, and further information could narrow it down.

P.S. Here is the best comment on Hacker News. Someone tweaked my model to understand it better and plans to use his own model to show why he disagrees with me. The world needs more scarmigs.

P.P.S. I'm going to quote tptacek on Hacker News who clearly explains my point:

Stucchio didn't propose a magic python script that answers the question of whether we should a basic income or basic job. He simply proposed a tool for making the debate more concrete. The debate still happens. It just gets less stupid.

Useful References

I've found the books Monte Carlo Methods in Financial Engineering and Markov Chain Monte Carlo to be good introductory books on this topic. Admittedly, I'm a mathematician, and these might be a bit inaccessible to some.

Also interesting is a discussion between various econobloggers on the role of mathematics in economics. Here is Noah Smith arguing against it, Paul Krugman (also here) arguing in favor of it, and Bryan Caplan also argues against it. See also this excellent post on the Magic, Maths and Money blog. As one might gather from my "shut the fuck up and write some code" comments, I'm solidly in the Krugman camp on this one. (No, I never thought I'd say that either.)