My business partner likes to tell me a story about a pair of shoes she purchased. First she saw the shoes in a TV commercial. Then one of her friends bought the shoes and showed her a picture on Facebook. She then browsed to the online store selling the shoes, but did not purchase. She was retargeted for a few days, with the tagline "you know you want them". Eventually she went directly back to the store and purchased the shoes.

Attribution theory is the process of asking the following question - who gets credit for the sale? The TV commercial, social media, "direct", or the retargeter? There are a variety of fairly standard models for this.

- Last Click Attribution. This says that the last advertiser to touch the customer is the one who deserves 100% of the credit for the sale. This model is surprisingly popular.

- First Click Attribution. This says that the first advertiser is the one who deserves 100% of the credit. This model is unpopular, but exists out in the world.

- Linear Attribution. This allocates credit for the sale to all advertisers equally. This model, while simple, is a-priori one of the better ones in my opinion. That's not to say it's a great model, but there are mathematical reasons to believe that it's not a terrible approximation.

- Temporal attribution. This is a scheme along the lines of 50% for the last ad, 25% for the second to last, 12.5% for the third to last, etc. It's also a pretty good scheme, and I suspect it might be a better approximation to reality than linear attribution.

The core problem with all attribution models is that they are attempting to guide decisions about where to spend advertising. But an attribution model asks the wrong question - it's asking how to give credit for your existing sales. The right question to ask is where your next sale will come from.

A Motivating Example

Suppose we know concretely how our sales respond to advertising dollars. Specifically, suppose we know the exact relation between sales and advertising. Let $@ x $@ represent the money spent on TV and $@ y $@ represent the money spent on radio. Then suppose sales are given by:

In real life we'll never know this, of course. But it's illustrative to have a fully explicit mathematical model to explore the concept.

Now suppose that we've currently devoted $10 to TV advertising and $0.5 to radio advertising. What can we deduce? First of all, sales will be 97.

For simplicity we'll assume all sales are due to advertising. We'll assume 92 people saw TV ads only, 2 people saw a TV ad then a radio ad, and 3 people saw radio ads only. With last touch modelling, we might discover that 5 sales were due to radio ads (2 of those customers also saw a TV ad) and 92 are due to TV. With linear attribution, we'd attribute 93 sales to TV and 4 to radio.

With linear attribution it looks like radio accounts for 5.1% of sales and 4.7% of advertising spend. Good deal! In contrast, with linear attribution, it looks as if radio accounts for only 4% of sales but costs 4.7% of ad spend. So in either case, it looks like sales are roughly proportional to ad spend, but we can tweak things a little bit around the margin.

Surprise - you've just discovered another $1 for the advertising budget. Where should you spend it?

Put it all into radio. Sales will go up from 97 to 220!

That's not really clear from attribution models. The attribution models suggest that either TV or radio is marginally better than the other, depending on which you choose.

The power of marginal thinking

Instead of thinking in terms of giving credit for sales we've already achieved, we need to think on the relevant margin. The relevant margin is the next sale. The right question to answer is "how do I maximize sales right now?"

We define the Marginal Return on Advertising or MRA as the allocation which will maximize future sales. So given that we've already spend $10 on TV and $0.5 on radio, the question is how to allocate that last $1 in order to increase sales the most?

There are a couple of ways to answer this quesiton.

Brute Force

Given that we have an explicit form for our return on advertising, we can simply brute force it, just make a table of possible allocations:

- TV gets an extra $1, radio gets an extra $0: $@ S(11, 0.5) = 100 \cdot \ln(1+11)\ln(1+0.5) = 100.7 $@

- TV gets an extra $0.5, radio gets an extra $0.5: $@ S(10.5, 1.0) = 100 \cdot \ln(1+10.5)\ln(1+1.0) = 169 $@

- TV gets an extra $0.0, radio gets an extra $1.0: $@ S(10, 1.5) = 100 \cdot \ln(1+10)\ln(1+1.5) = 219 $@

A picture

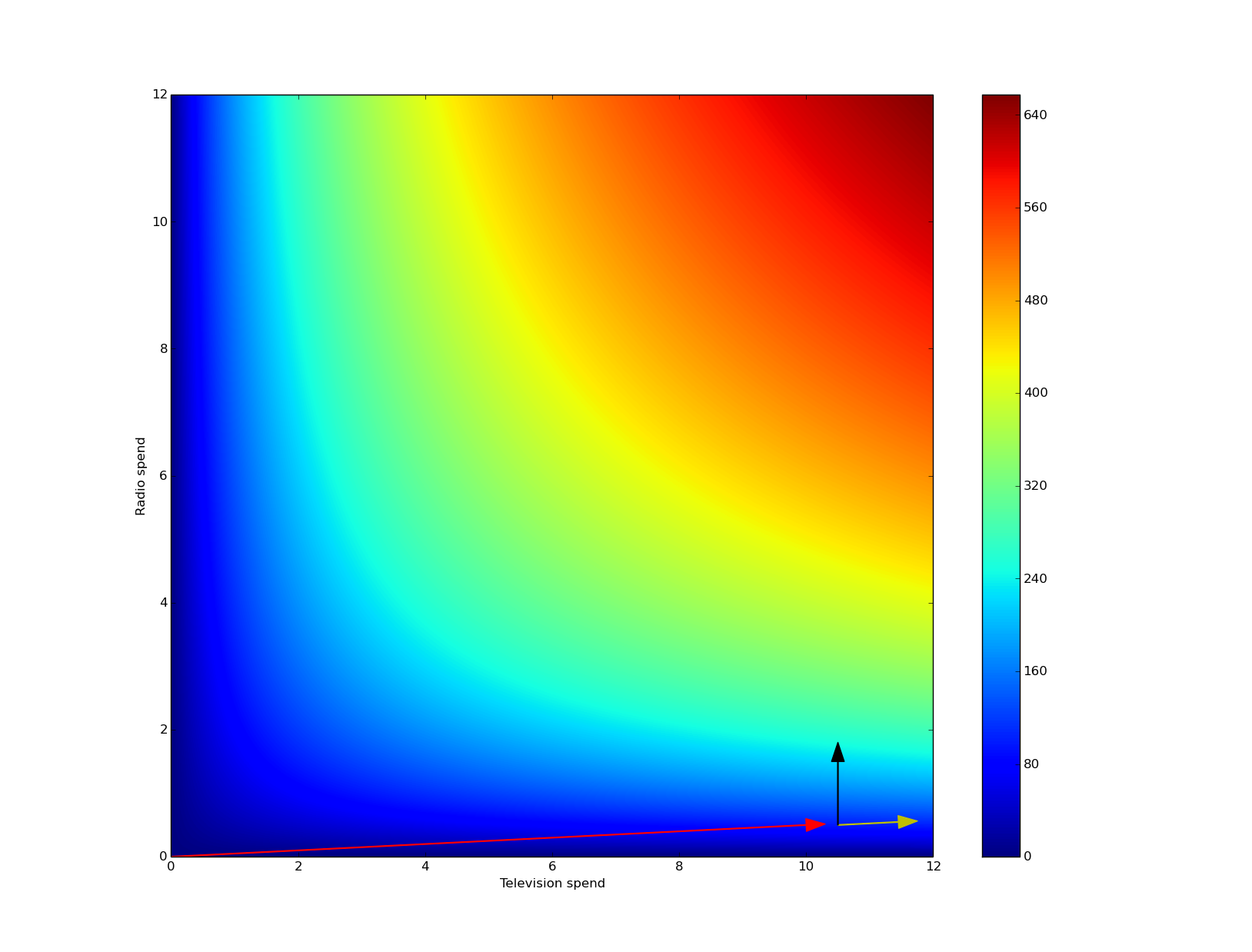

So now I'll draw a picture. A point on the graph represents an allocation of capital into different advertising channels - for example, the point \(@(2,3)\)@ represents 2 dollars in television and 3 dollars in radio. The color represents how many sales we'd receieve with that allocation. More red means more sales.

The red arrow represents our original spend - $10 on TV and $0.5 on radio. Now we've got an additional $1 - what to spend it on? The yellow arrow represents throwing money in the direction of attribution theory. This will increase sales, but not by a lot.

In contrast, the black arrow represents the direction maximizing the Marginal Return on Advertising - throwing that additional $1 into radio. And that shifts us from the dark blue to the light blue region of the picture.

In short, attribution theory measures how you got to where you are, where as Marginal Return on Advertising measures where you should go next.

Calculus

To use calculus, we compute the gradient of our sales function:

We then evaluate this at \(@(x,y)=(10,0.5)\)@. The answer is: $@ \nabla S(x,y) |_{(10,0.5)} = [0.037, 1.60] \approx [0,1.6] $@. Looks like increasing radio spend will get a much bigger bang for buck than TV spend.

Let me call this quantity the marginal return on advertising or MRA. More precisely, for TV, the MRA is

and for radio is

The Big Idea

The advertising channel that works the best for our current sales is not necessarily the advertising channel which is the best use of additional dollars. Attributing credit for past sales is not the same thing as determining how to allocate/reallocate future advertising spend. The right concept is Marginal Return on Advertising or MRA, which is the amount by which sales will increase if your pour additional money into some particular channel.

See also: The concept of marginal return on advertising is also the big idea behind Gabriel Weinberg's Traction Book. Weinberg's framework essentially consists of running experiments that increment x to see if it increases sales/traction, and if that fails increasing y, and repeating until a direction of rapid growth has been found.