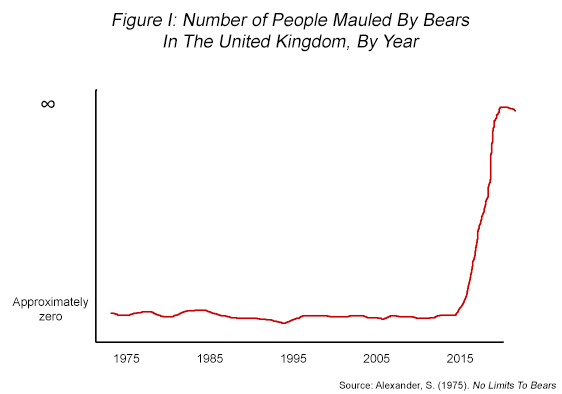

In a groundbreaking work back in 1975, Scott Alexander made a prediction of dire environmental consequences by the year 2015 if we don't change our behavior. His book No Limits to Bears predicts an upcoming bearpocalypse and so far his predictions seem pretty accurate - I ran a statistical test and his predictions agree with the data with p<0.05.

Strangely, I don't think I've convinced any of my readers to start investing in bear traps. Why is that?

In principle Scott Alexander's bearpocalypse theory is falsifiable - we just wait until 2015 to see if hungry bears devour the world. But that doesn't really help us decide whether to start the mass production of bear traps today.

Pastafarian Cosmology and the limits of falsifiability

Consider now a cosmological theory - Pastafarian Quantum Creationism. The theory claims the following. Let $@ H $@ be a standard quantum mechanical Hamiltonian. Then the wavefunction of the universe is described by:

where

The term $@ P(t) $@ represents the creational influence of his noodly goodness on the universe, specifically the creation of life.

Even in principle, no experiment can ever distinguish Pastafarian Quantum Creationism (PQC) from ordinary quantum mechanics, at least for experiments run after 5,234BC. That's because if the initial conditions are identical, and \(@P(t) = 0\)@, the wavefunctions must remain the same.

So in principle, any scientific experiment which forces us to reject PQC must also force us to reject QM.

Even more troubling is the fact that we also cannot run any scientific experiment to reject Heretical Pastafarian Quantum Creationism (HPQC) which asserts that his noodly goodness stopped influencing the world in 4,983BC rather than 5,234BC.

Kolmogorov Complexity

Consider an abstract computer, for example a Turing Machine. In computing, a string S is said to have a Kolmogorov Complexity of k bits if the shortest program that can be used to compute S has k bits.

For example, on the Python interpreter the string abababababababababababababababab has complexity of 7 bytes, since it can be represented as the 7 byte program 'ab'*16. In contrast, the string 4c1j5b2p0cv4w1x8rx2y39umgw5q85s7 probably has complexity of 32 bytes since it cannot be similarly reduced.

We can similarly define a concept of Kolmogorov Complexity for a theory - for example, we can define it as the number of bytes necessary to represent the equations in LaTeX. The key idea here is that some theories are more complex than others. For example PQC:

is more complex than QM:

A prior for theories - how to explain Occams Razor

Occams Razor is the general idea that simpler theories are more likely to be true. I'm going to describe this more formally via a Bayesian epistemology.

Let $@ T $@ be any theory of the world, and let $@ k(T) $@ represent it's complexity. I want to construct a probability distribution over the set of all possible theories - the goal is to say that simpler theories are more likely. So suppose I had a measure over the space of all possible theories, $@ dT $@, together with a density function $@ p(T) $@.

In words, I want to declare that the probability of some theory of complexity b being true is lower than that of some theory of complexity a being true if $@ a < b $@. In mathematics, we would impose this condition on our prior:

Also, we need to intrinsically assign priors to each parameter choice. For example in Scott Alexander's bearpocalypse theory, there are two important parameters - the year 2015, and the use of bears (rather than other animals, e.g. jaguars) in destroying the world. So within the universe of $ANIMAL-pocalypse theories, we would need a prior on animals and a prior on the given year.

So now lets consider the following set of theories (with $@ S(z) $@ being an S-curve - $@ S(z < 0) = 0 $@ and $@ S(z > 1) = 1 $@):

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = 0 $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot \textrm{bear density} \cdot \textrm{human density} $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2013) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2014) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2015) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2016) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2017) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2018) $@

- Etc.

Apriori, the most likely of these theories is (1), since it is simpler than the rest. The second most likely theory is (2), being simple multiplication.

The remaining theories are each individually considerably less likely, since there are so many of them. They should all be roughly equivalently equal in probability, since they are functionally not different from each other, but that isn't exactly possible since there isn't a uniform distribution that applies to all time periods. Lets gloss over that detail and suppose the priors on $@ \textrm{const} $@ and year are simply very wide.

This is far from an exhaustive list of theories, but it's illustrative. So concretely, lets assign the following priors:

- 0.5

- 0.25

- 0.25 / 100,000 = 2.5e-6

- 0.25 / 100,000

- 0.25 / 100,000

- 0.25 / 100,000

- Etc.

I.e., we are saying that if a bearpocalypse occurs, we have no particular reason to believe it would happen in 2015 - it could have happened with equal probability during any of the previous 50,000 years, or it might equally well happen at some point in the next 50,000 years.

Now what?

(In reality, this is of course a wildly high estimate on the bearpocalypse probabilities, and I'm completely ignoring things like the jaguarpocalypse. I'm keeping things simple.)

Looking at the evidence

Now we need to look at the evidence. To begin with, we can immediately reject theory (1) - bear attacks do occur. We can also reject (3) and (4), as well as the large family of theories "bearpocalypse at $@ t < 2014 $@". So the remaining valid theories:

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot \textrm{bear density} \cdot \textrm{human density} $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2015) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2016) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2017) $@

- $@ \textrm{Bear maulings} = \textrm{const} \cdot S(t - 2018) $@

- Etc.

If we apply Bayes rule (which in this case simply means renormalizing), we find the following posterior probabilities:

- 0.6666

- 6.66e-6

- 6.66e-6

- 6.66e-6

- Etc.

What to do in practice?

Now lets get to the core question: should we invest in bear traps?

To answer that, we want to know the probability of a bearpocalypse occuring anytime soon. The probability of a bearpocalypse occurring in 2015 is only $@ 6 x 10^{-6} $@. The probability of a bearpocalypse occurring before 2020 is only $@ 4 x 10^{-5} $@. So it looks like those bear traps are a pretty bad investment.

Conclusion - can we really reject Pastafarian Quantum Mechanics?

Much as with the bearpocalypse theories, we can reject certain flavors of Pastafarian Quantum Mechanics. Specifically, we can reject theories which have $@ P(t) != 0 $@ for $@ t > \textrm{modern experiments} $@. But we can't falsify most of the possibile pastafarian theories which postulate a quantum term which is currently zero - all future experiments will be identical.

Any rejection of pastafarian cosmology and the more sophisticated variants of (Christian) biblical creationism [1] cannot be based on falsifiability. It must be based on other principles, such as Occams Razor.

And in my view, a rational Bayesian has no grounds for rejecting such theories. They have some intrinsically small prior probability of being true, and because their empirical predictions agree with simpler (non-pastafarian) theories, they can in principle never be rejected. They can, however, be glossed over as a computational heuristic. Because their empirical predictions about all future experiments agree completely with simpler theories (e.g., ordinary quantum mechanics), we can simply focus all our mental effort on analyzing the simpler theory.

So we can certainly declare Pastafarian Quantum Mechanics to be a useless theory. But it's rather more difficult to declare it to be wrong.

[1] I have encountered a creationist physicist who I will not name. His faith caused him to apply a very high prior to certain creationist theories - fossils and such were explained as god fooling around and testing people's faith. He's a rather good physicist, and if his predictions about future experiments differ from mine, it's probably because I made a computational mistake.