It's a widely cited fact that Uber has continually lost money since it started. Uber opponents widely cite this fact hoping that once the VCs stop investing, Uber will collapse and we can return to the era of yellow cabs. Another stylized fact about Uber is that it's profitable in many cities. In this post I'm going to do some basic financial modeling, and explain why these two facts make me very bullish on Uber.

The economics I'm going to describe are actually pretty well known in the field of SaaS, where they are commonly called the SaaS cash flow trough.

The SaaS Trough

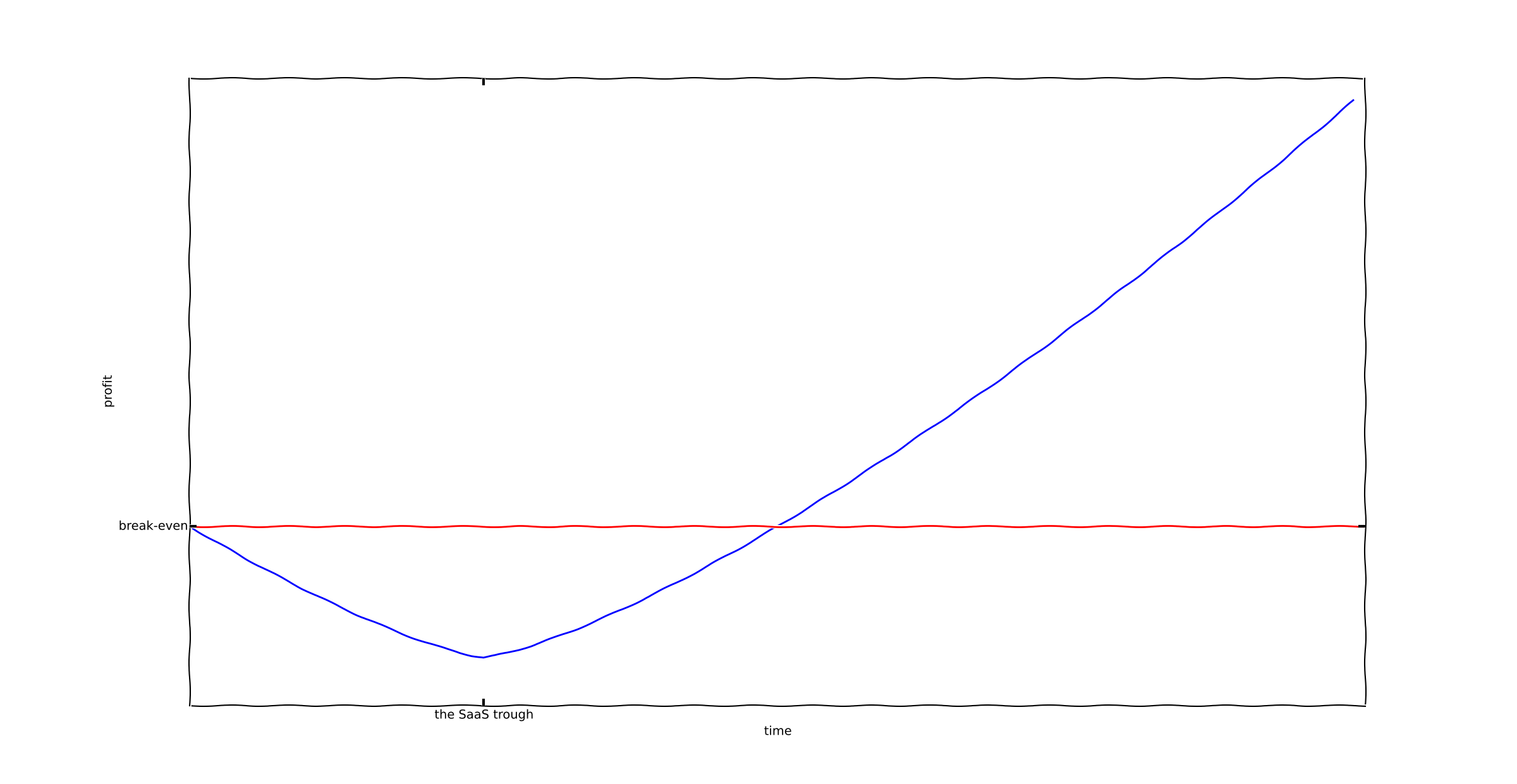

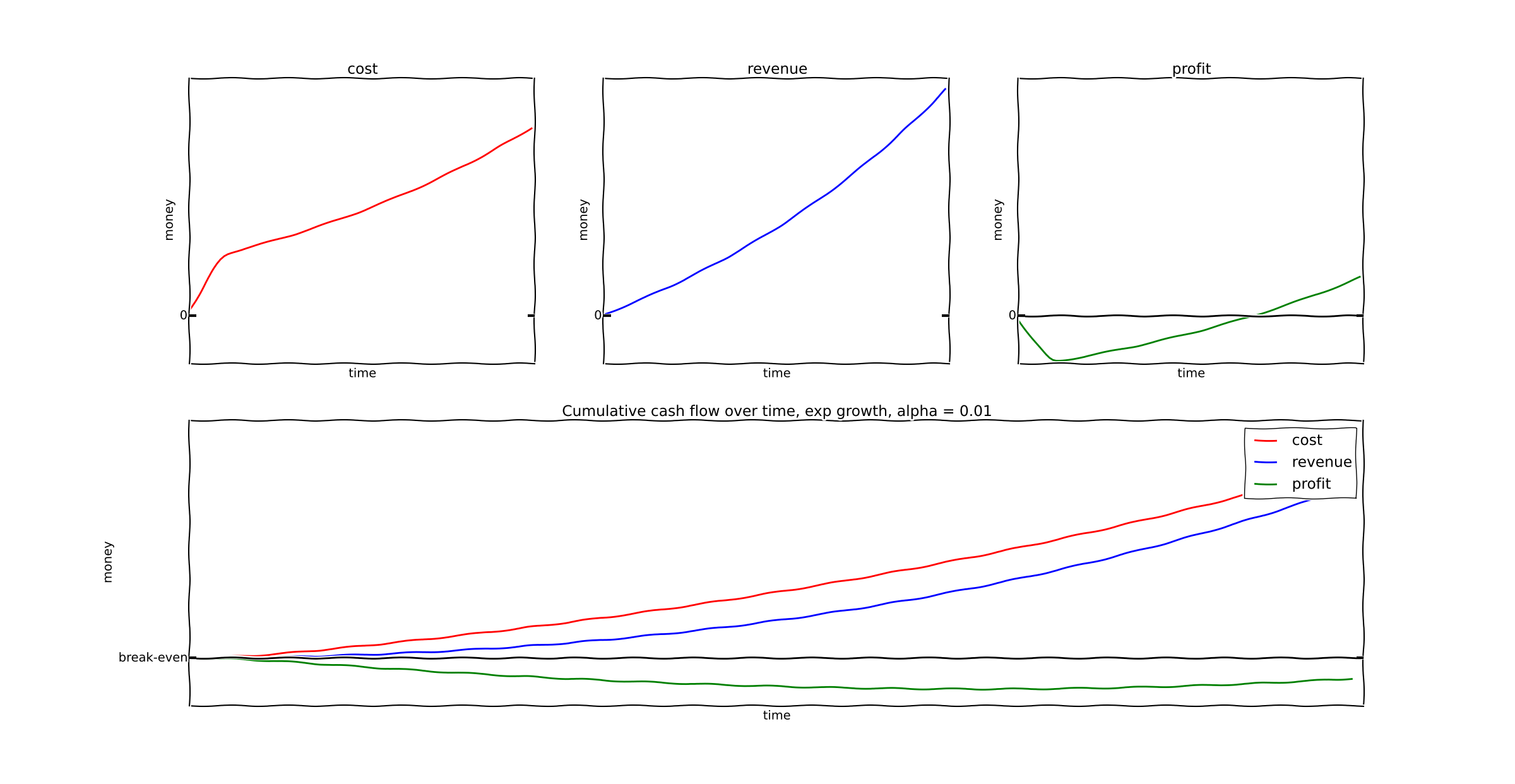

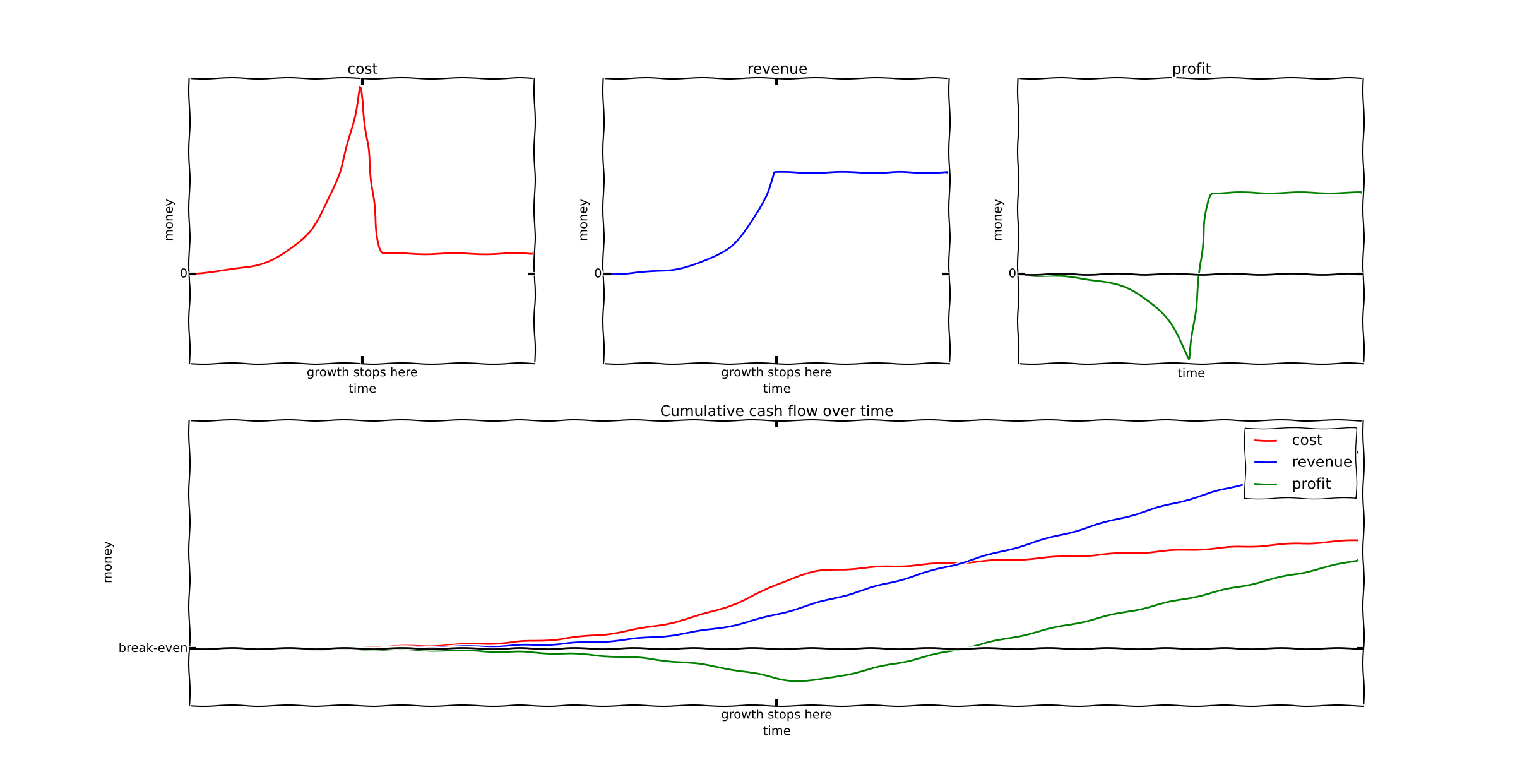

The SaaS trough, roughly speaking, looks like this:

This is an extremely common cash flow diagram across a wide variety of SaaS companies. The trough portion is the time when such companies are raising repeated VC rounds, while simultaneously witnessing revenues rising and costs rising even faster.

The key cause of this cash flow graph is a fairly universal feature of SaaS companies, and it's also a feature such companies share with Uber. The key cause of this is the high cost of acquiring a customer, the very low costs of servicing the customer, and the fact that profit happens over time.

As can be demonstrated by the cumulative cash flow at the end of this graph, we have a profitable business. You can put a fixed amount of money in, and over time you'll pull a larger amount of money out. But early on losses are quite high.

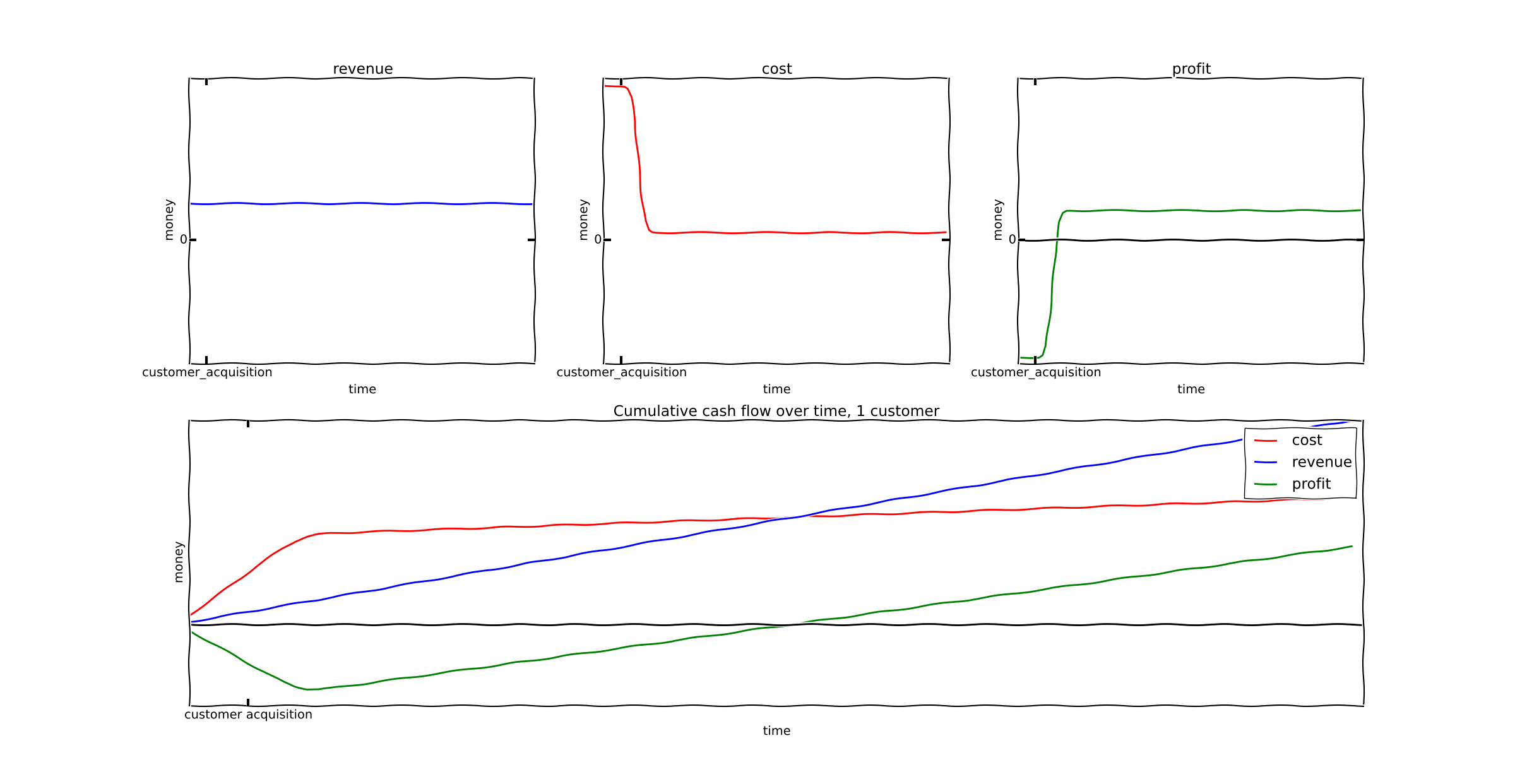

In the example I've graphed, we have the following (stylized) data:

- customer acquisition cost = $200

- customer cost per time period = $1

- customer revenue per time period = $5

In terms of python code, I did the following:

cost = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

cost = (1+erf((10-t)/2.0))*10+1

revenue = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

evenue[:] = 5

profit = revenue - cost

Roughly speaking, I'm assuming that a customer costs approximately $200 for a short time at the beginning of their lifetime, and then their costs drop to $1. They generate a constant $5 in profit.

This means that for an initial expense of $200, you will receive revenues of $400 (and profit of $200) after 100 time units. Sounds awesome, right? Any VC would wish to invest in this.

The SaaS trough continues for a long time

The trough I drew above is the cash flow for a single customer.

But suppose there is a wide open market - a huge number of customers to acquire. Lets do some more detailed modeling.

First, I'll define the following function which models a single customer's cash flow over time. This assumes the customer is acquired at a time t0:

def customer_cash_flow(t, customer_acquisition_time):

cost = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

cost = (1+erf((customer_acquisition_time+10-t)/2.0))*10+1

cost[where(t < customer_acquisition_time)] = 0.0

revenue = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

revenue[where(t >= customer_acquisition_time)] = 5

profit = revenue - cost

return (cost, revenue, profit)

Then I'll assume that every 5 units of time, the business gains a new customer:

t = arange(100)

cost = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

revenue = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

profit = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

for i in range(0,100, 1):

c, r, p = customer_cash_flow(t, i)

cost += c

revenue += r

profit += p

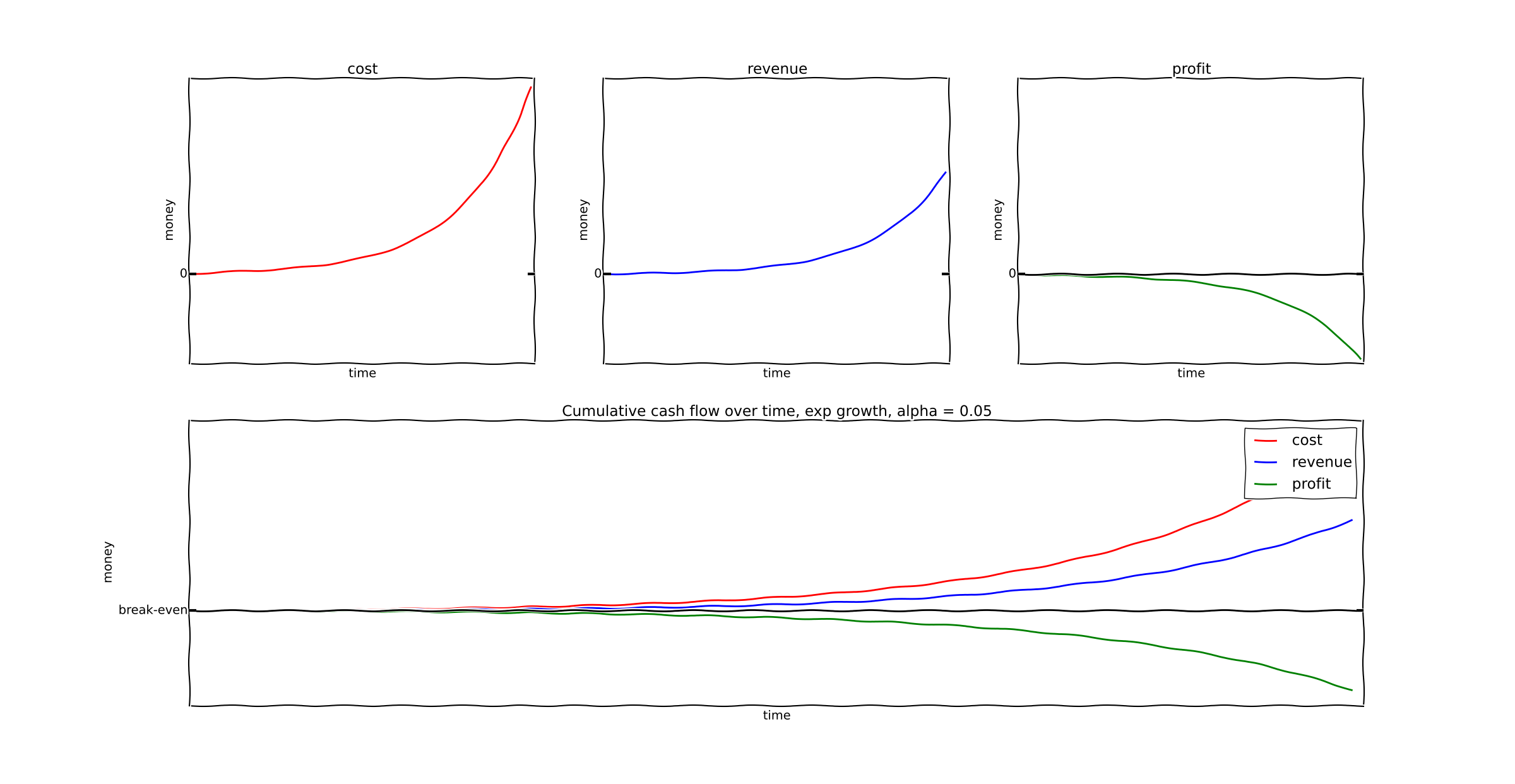

Here's a graph of the result. A new customer is added at every unit of time.

The key point here is that the SaaS trough lasts a much longer time than before.

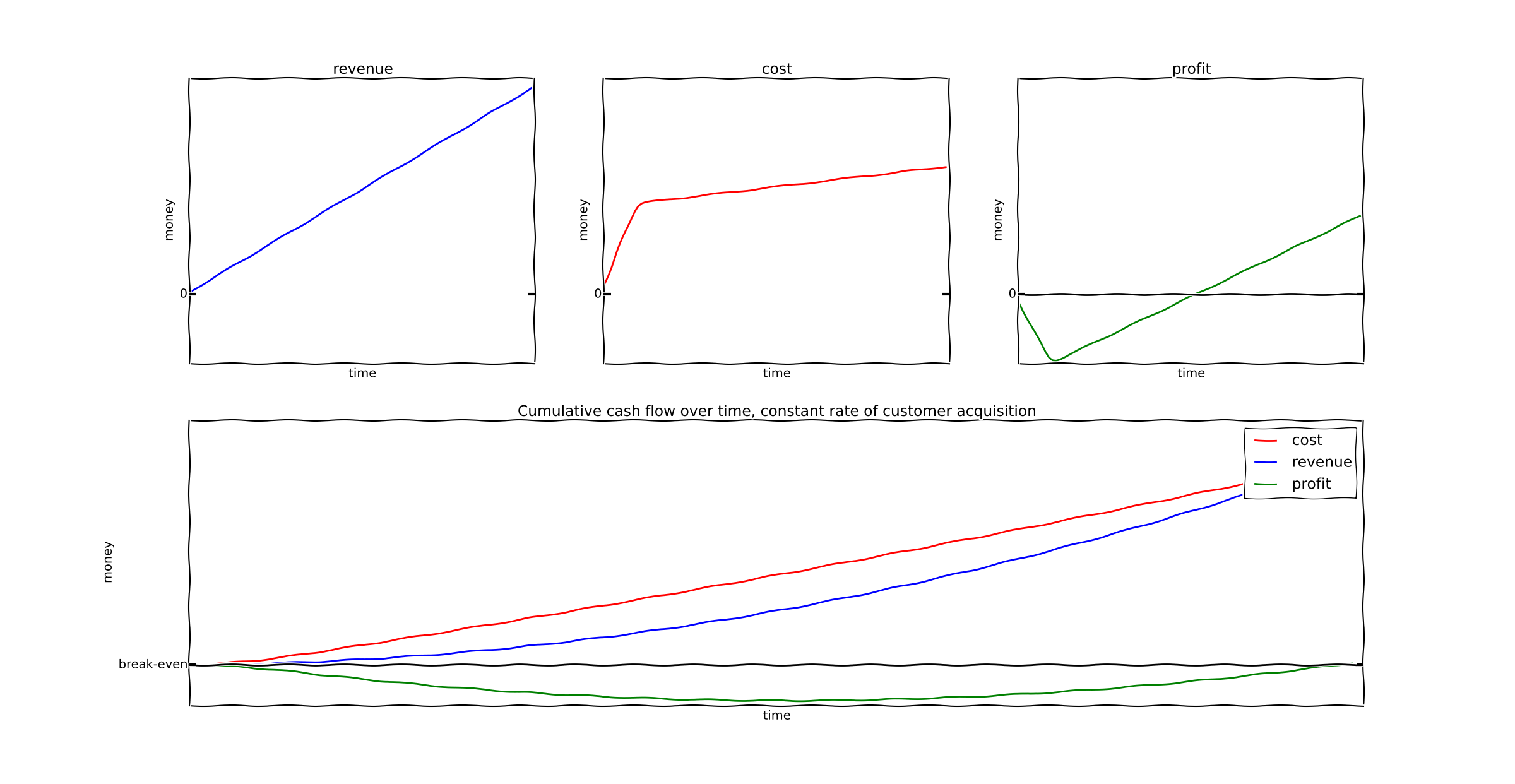

Exponential growth

In the example above, I assumed the rate of customer acquisition was linear. Every 5 days a new customer is added.

But in reality, exponential growth is the ultimate goal of both Uber and many SaaS companies. So what happens if we assume exponential growth?

In this case we just change our model to include an exponential growth rate alpha:

alpha = 0.05

for i in range(0,tmax, 1):

c, r, p = customer_cash_flow(t, i)

cost += c*exp(i*alpha)

revenue += r*exp(i*alpha)

profit += p*exp(i*alpha)

With a slow growth rate (1% per time period), our hypothetical company becomes profitable eventually:

But with a faster growth rate of 5% per time period, losses will continue for as long as exponential growth does. In fact, losses will grow exponentially!

How does this apply to Uber?

This model applies to companies with a high customer acquisition cost and a very low customer maintenance cost. Typically this will be a SaaS company with a high-touch sales process; lots of marketing, inside sales, that kind of thing. I claim that Uber has similar economics; when Uber opens up a new city they need to spend a lot of money onboarding drivers and fighting corrupt politicians. (I'm told by an inside source that actually acquiring customers is almost "if you build it they will come" easy.)

So the microconditions of our model appear to apply to Uber.

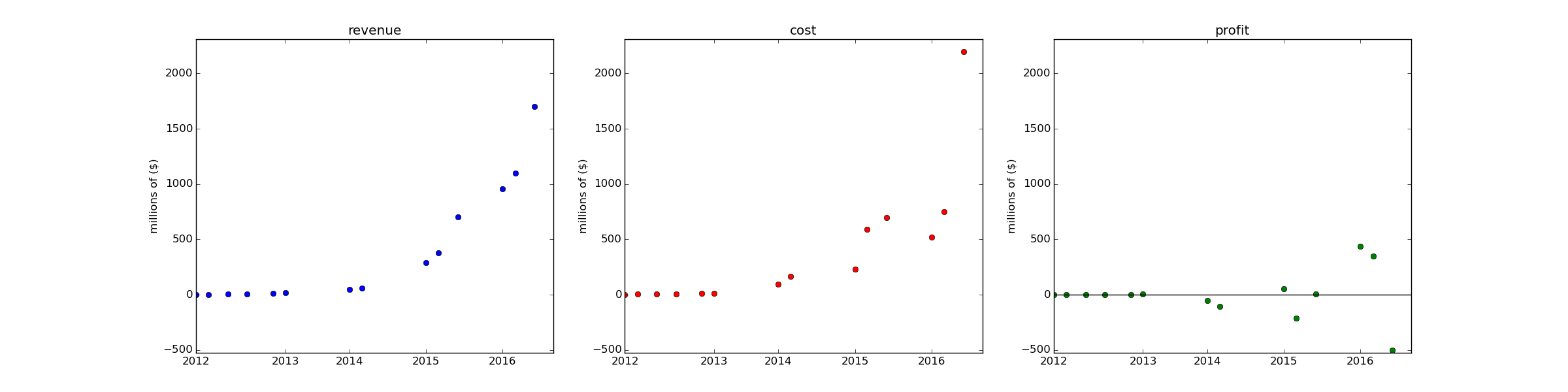

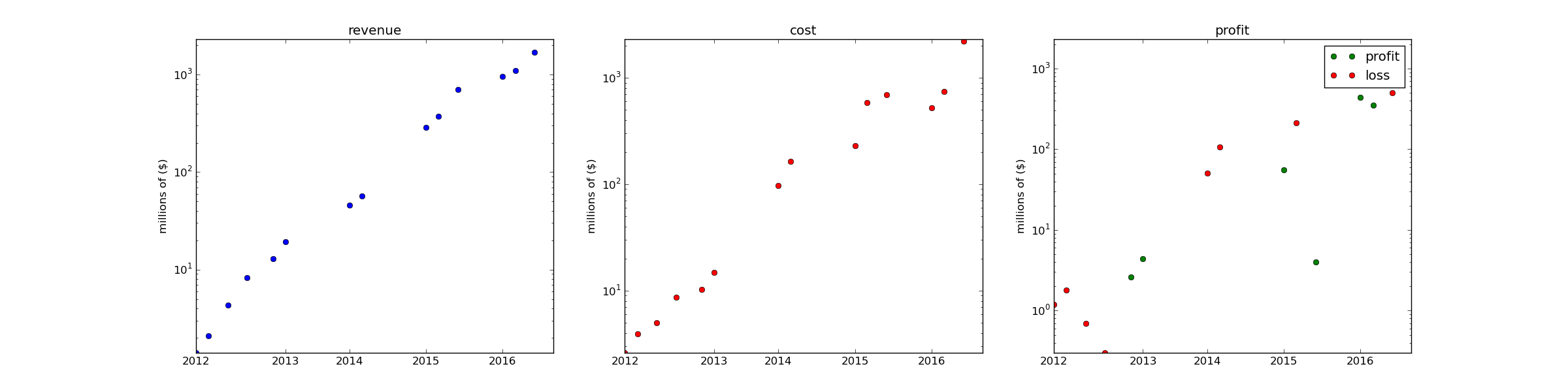

Furthermore, if you graph of Uber's revenue vs it's losses, with numbers taken from Business Insider, you see that the outputs of the model also appear accurate:

If we plot the same data on a logscale we can see a very clear rate of exponential growth:

Bloomberg provides similar information.

So all the data we can see concerning Uber suggests that Uber is, in fact, in the "lose exponential amounts of money" phase of the SaaS growth curve.

Testing the model via Cohort Analysis

There's another test of the model that we can run.

Another implication of the model is the following. Every single customer acquired by the growing company is profitable over the long haul. The first customer breaks even after 50 units of time, and is profitable thereafter. But the business as a whole is losing money because the profits are spent on acquiring customers 2, 3 and 4 (who will eventually be profitable).

So in our model, the older cohorts (e.g. customers acquired 200 units of time ago) should be profitable, and losses should be concentrated among the newer (and much larger) cohorts.

In fact, we observe this exact behavior with Uber. In Uber's older markets, it is profitable, but it is losing money on newer markets where it's attempting to grow.

What happens when growth stops?

One common question asked about Uber is the following. What happens when growth stops? This could happen in multiple ways:

- VCs might get cold feet and pull out, because Travis Kalanick is such a big mean jerk.

- Uber may reach a natural saturation point when it's acquired all customers who could be acquired.

At this point, does the whole house of cards collapse?

The answer is that it doesn't have to. I've run the model again, but I'm assuming at a certain point our company stops acquiring new customers. This has two effects:

- Growth stops.

- The cost of customer acquisition drops.

In python, I've done this:

tmax = 200

t = arange(tmax)

cost = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

revenue = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

profit = zeros(t.shape, dtype=float)

alpha = 0.05

for i in range(0,100, 1):

c, r, p = customer_cash_flow(t, i)

cost += c*exp(i*alpha)

revenue += r*exp(i*alpha)

profit += p*exp(i*alpha)

So while we're extrapolating the graph out to t=200, growth stops at t=100. The result is as follows:

Basically what happens is at the point when customer acquisition stops, the company becomes profitable. Customer acquisition was the sole reason for losing money in an otherwise profitable business.

At this point new investments should also stop. Sometime after this Uber can become a stable, boring, long term profitable business. At this point it can be valued according to ordinary Wall St. utility company metrics, and the VCs who've invested can take their profits.

Conclusion

I have no insider knowledge on whether Uber is actually long term profitable on individual cohorts, beyond what they've told the media. I also have no knowledge of whether Uber can successfully make the transition from growth to utility; if a company fails to cut their acquisition costs at the right time, they may crash and burn regardless of their per-customer profitability.

However, the point I want to make in this article is the following. Uber's current trajectory is perfectly consistent with the trajectory that many currently profitable SaaS business have taken. There is no fundamental reason to believe that Uber will crash and burn, either when growth stops or VCs stop funding it. Uber does not appear to be on VC-funded life support - by all indications it's on VC-funded hypergrowth, and can probably eventually become profitable once that growth stops.

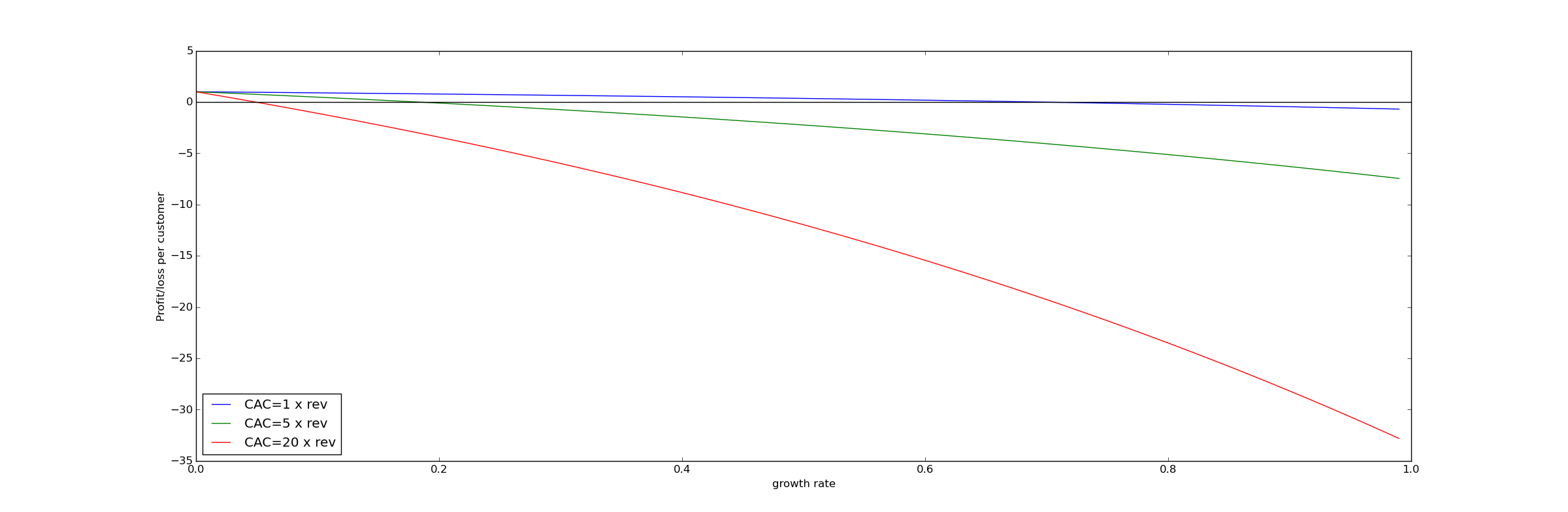

Appendix - more mathematical analysis of hypergrowth

Unless you like formulas, skip this section. I'm building a discrete time model to understand exactly when hypergrowth implies exponential unprofitability.

Consider a discrete time model. Assume that a customer generates a profit of $1 for $@ t > 0 $@ and costs $@ A $@ at $@ t = 0 $@. Assume further that the company has $@ e^{\alpha t } $@ customers at time $@ t $@. At time $@ t $@ the company has $@ c $@ customers. Based on hypergrowth, at time $@ t + 1 $@ the following happens:

- The company acquires \(@c (e^{\alpha} - 1)\)@ customers.

- The company gains $@ c $@ units of revenue from older customers.

- The company loses $@ c (e^{\alpha} - 1) A $@ due to customer acquisition costs.

The profit/loss $@ p $@ is therefore:

$@ p = c - c(e^{\alpha} - 1)A = c (1 - A(e^{\alpha}-1)) $@

If $@ A(e^{\alpha}-1) < 1 $@, then the company will have profit growing exponentially. On the flip side, if $@ A(e^{\alpha}-1) > 1 $@, then the company's losses will grow exponentially.

What's really important to note here is that faster growth implies greater losses!