With Andrew Yang's presidential candidacy moving forward, people are discussing basic income again. One common meme about a Basic Income is that by removing the implicit high marginal tax rates that arise from the withdrawal of welfare benefits, disincentives for labor would be reduced and therefore a Basic Income would not reduce labor supply. In this blog post I provide both empirical and theoretical evidence why this conclusion is false.

In particular, I review the experimental literature, which suggests a Basic Income will result in approximately a 10% drop in labor supply. I also review standard economic theory regarding diminishing marginal utility, which provides a clear theoretical reason why a Basic Income would reduce labor supply.

Finally, I extrapolate the data from the 1970's Basic Income experiments to the contemporary era. In particular, I consider a counterfactual history, taking the employment effects from past experiments and applying them to contemporary employment rates.

Empirical evidence: 5 North American Experiments

Let me begin with the empirical evidence. There have been 5 experiments on either Basic Income or Negative Income Tax in North America. I'll discuss each of them in turn, focusing on the labor force effects.

Seattle/Denver Income Maintenance Experiment

This experiment measured the effect of a Negative Income Tax as compared to the welfare programs (AFDC, Food Stamps) available at the time. The experiment ran from 1970-1975 in Seattle and 1972-1977 in Denver. The benefit of the plan was an unconditional cash transfer, assigned randomly at various levels, with the maximum transfer being equal to 115% of the poverty line.

The sample was focused on lower income Americans, and aimed to collect representative data on Whites, Blacks and Chicanos (in Denver only) - this resulted in the minority ethnic groups being significantly overrepresented. There were also two variations - a 3 year treatment group and a 5 year treatment group.

The net result on labor supply is the following:

- Husbands reduced their labor supply by about 7% in the 3-year treatment group and by 12-13% in the 5 year treatment group.

- Wives reduced their labor supply by about 15% in the 3-year treatment group and by 21-27% in the 5 year treatment group.

- Single mothers reduced their labor supply between 15 and 30%.

- The labor supply reduction typically took 1 year to kick in, suggesting a shorter experiment might have missed it.

- The fact that the reduction is larger in the 5 year group than the 3 year group suggests anticipation effects - people know that they will have guaranteed income for several years so they plan for long term work reductions.

The experiment tracked both treatment groups for 5 years, and in the final 2 years the 3 year treatment group recovered most of their labor market losses.

An additional interesting effect observed is a higher rate of divorce in the treatment groups.

Mincome: Manitoba Basic Annual Income Experiment

The Mincome experiment is the one most commonly cited by fawning journalists. For example, here's how Vice describes it:

> The feared labor market fallout—that people would stop working-didn't materialize... "If you work another hour, you get to keep 50 percent of the benefit you would have gotten anyway, so you are better off working than not."

This framing is typical in mainstream journalism:

> 'Politicians feared that people would stop working, and that they would have lots of children to increase their income,' professor Forget says. Yet the opposite happened: the average marital age went up while the birth rate went down. The Mincome cohort had better school completion records. The total amount of work hours decreased by only 13%.

This framing is weird, because a 13% decrease in labor supply is actualy pretty big. A differences in differences analysis of Mincome suggests a treatment effect of about 11.3%. There are also subgroup analysis suggesting that this effect might be driven more by women than men, but these are prone to small sample effects as well as the Garden of Forking Paths.

One interesting result from Mincome is that about 30% of the effect of Mincome is likely to be socially driven rather than pure economics. The claim made is that if a Basic Income is given to everyone, reducing labor market participation may become socially normalized and this will drive further reductions in labor supply. This effect would likely not be measurable in a randomized control trial.

The Rural Income Experiment

Unlike the other experiments, this one was designed to measure the effect of Basic Income on rural people, in particular self employed farmers. Rural communities in Iowa and North Carolina were chosen and basic income equivalent to 50%-100% of the poverty level were given to people in the treatment group.

This experiment was on the small side; only 809 families entered and 729 remained in the program for all three years.

After controlling statistically for differences in observable characteristics of participants, the Rural Income Experiment showed an overall labor supply reduction of 13%. In this experiment the labor market effect was somewhat smaller for husbands (-8% to +3%) while being quite large for wives (-22%-31%) and dependents (-16% to -66%).

The widely disparate results reported across subgroups also suggest that the subgroup analysis is noisy and suffering from insufficiently large samples - not surprising given 809 sample familes split across 3 subgroups (NC Blacks, NC Whites and Iowa) plus 3 subgroup analyses per group (Husbands, Wives and Dependents).

The Gary Experiment

The Gary Experiment was focused on mitigating urban Black poverty. It was run from 1971-1974 and had a sample of 1800 families (43% of which were the control group). 60% of participating familes were female headed. Dual earning families were generally excluded from the experiment because their income was too high.

The size of the BI was pretty similar to those of the other experiments - 70% and 100% of the poverty level.

In this experiment, the work reduction was 7% for husbands, 17% for wives, and 5% for female heads of household. The reason the drop in female heads of household is low may simply be due to the fact that prior to the experiment, female heads of household only worked an average of 6 hours/week.

An additional effect of the BI was an increase in wealth inequality - higher earning married couples tended to save money and pay down debt while much poorer single mothers merely increased consumption.

The New Jersey Experiment

The New Jersey Experiment ran from 1967-1974. In this experiment the income levels ranged from 50% to 125% of the poverty line, and the experiment included 1350 randomly selected low income families in NJ and PA. Each family in the experiment received 3 years of Basic Income. As with the Rural Income Experiment, many subgroup analysis were performed (on a relatively low number of families per subgroup) and inconsistent results were obtained across subgroups.

The overall results were a reduction in labor supply (hours worked) by 13.9% for white families, 6.1% for black families and 1.5% for Spanish speaking families. The labor force participation rate reduction was 9.8%, 5% and +/- 6.7% for White, Black and Spanish speaking families respectively. (Due to the poor quality of the scan, I can't make out the digits after the decimal for black families or whether the effect is positive or negative in table 3.)

I do not endorse the level of excessive subgroup analysis they performed. In such a small sample they should have just done an overall analysis. But the experiment was designed in 1967 so I'll be forgiving of the authors - my viewpoint of their methodology is, of course, heavily informed by living through the modern replication crisis.

Empirical conclusions

The studies I've surveyed were all social experiments performed in the 1970's. As such, the treatment effects are comparing a Basic Income providing a roughly 1970-level poverty rate income to welfare programs from that era. These experiments were also performed in an era with significantly lower female workforce participation and higher marriage rates.

The experiments were also all pre-Replication Crisis, and as a result they feature excessive subgroup analysis, experimenter degrees of freedom, and for this reason I don't fully believe most of the fine grained effects these studies purport to measure.

However, there is one very clear and significant top line effect that is consistent across every experiment: a roughly 10% reduction in labor supply.

Theory: Why would this be true?

The common justification for why a Basic Income would not reduce labor supply is the following. Because a BI is given regardless of work, a person receiving a BI gains the same amount of money from working as they would gain if they did not work. This is often contrasted to means-tested welfare, which often has high implicit marginal tax rates due to the withdrawal of welfare benefits.

However, this verbal analysis ignores something very important: diminishing marginal utility.

In economics, people are modeled as making decisions based on utility - roughly speaking, the happiness you get from something - not on cash. And an important stylized fact, accepted by pretty much everyone, is that utility as a function of income is strictly concave down. In mathematical terms, that means that for any \(0 \leq \alpha \leq 1\):

Since more income is always better, we can also assume that \(U(I)\) is a strictly increasing function of income.

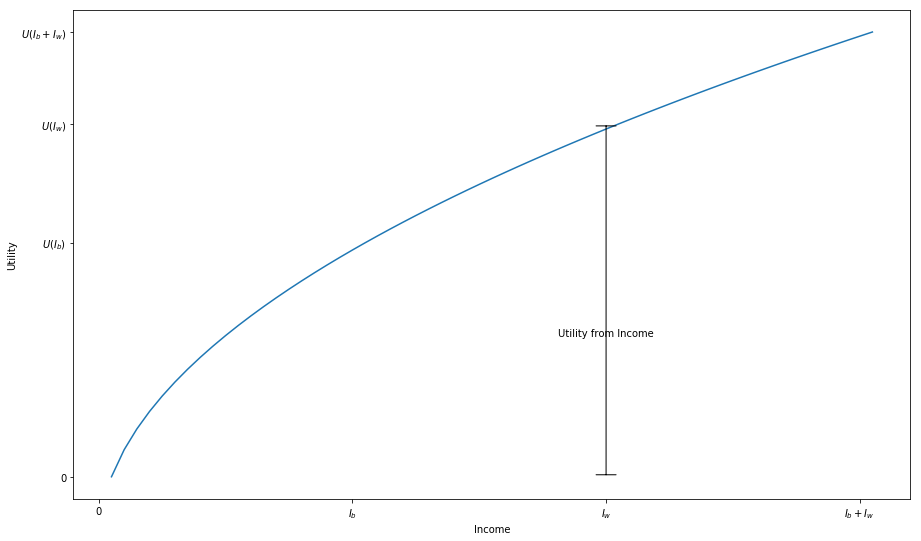

In pictures, this means that a person's utility function looks like this:

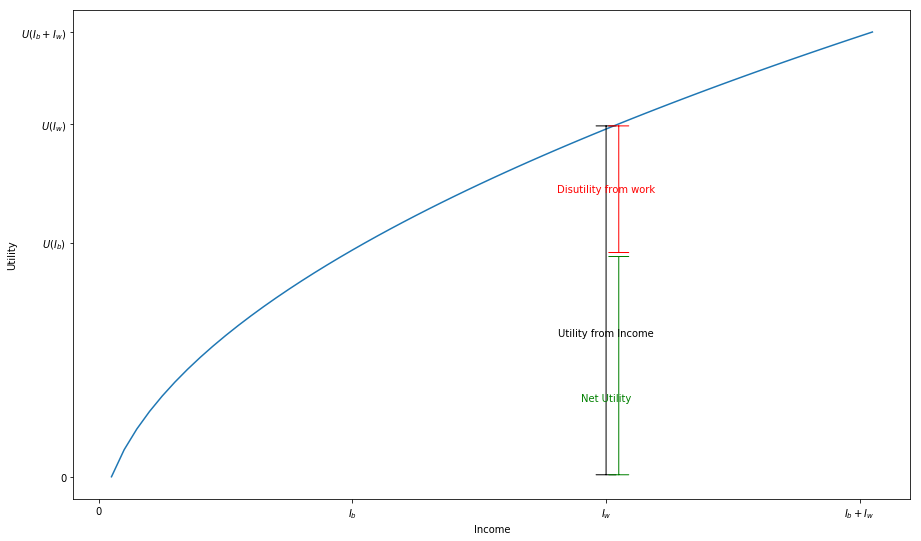

Now the choice to work is made by balancing the utility gained from income against the disutility from working:

Since the net utility is positive, this person will choose to work.

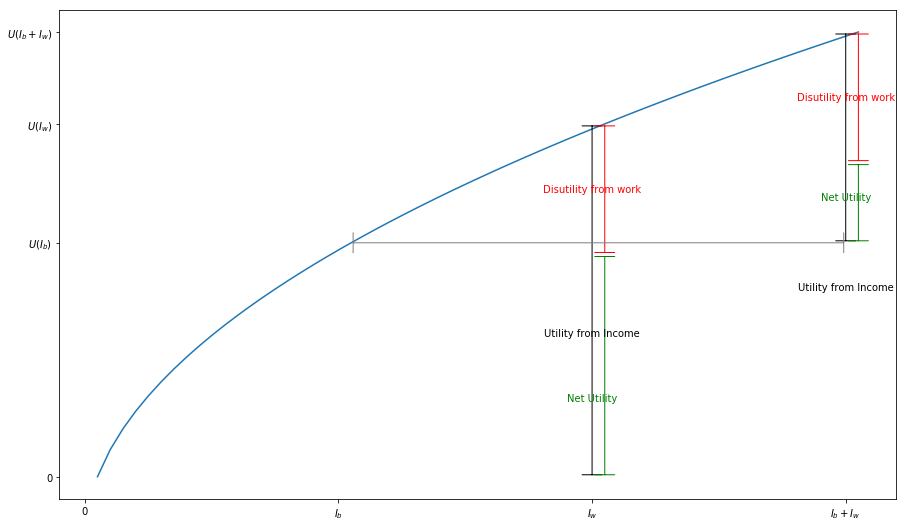

However, because the utility function is concave, if we start from a point further out (namely \(I_b\)), the utility gain from labor decreases. This can be illustrated in the following graph:

In the Basic Income regime, a person's utility gain from working is only \(U(I_b+I_w) - U(I_b)\), which is lower than \(U(I_w)-U(0)\).

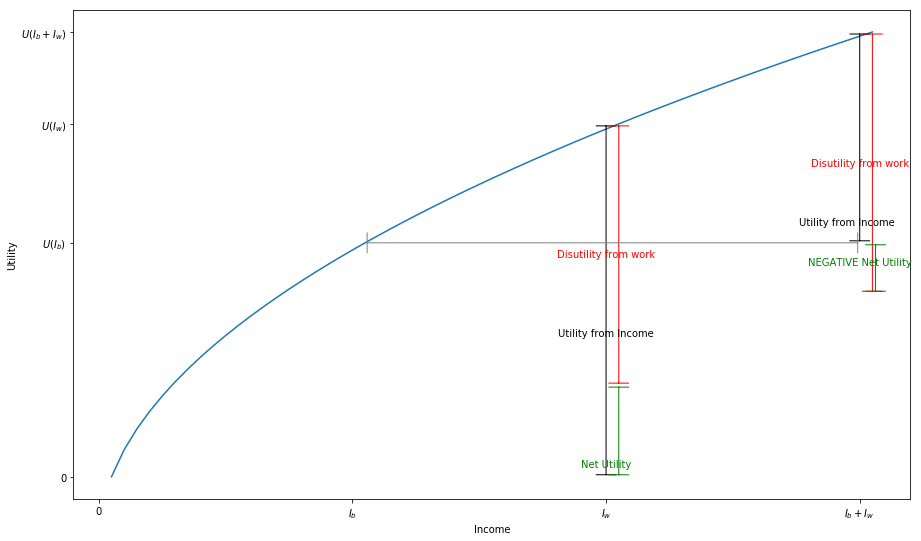

In some cases, this decrease will result in the net utility gain from work being negative:

These are the people who are deterred from working.

Now the graphs I've given above are just an example. The clever reader might ask if it is true for every graph. I will prove in the appendix that a Basic Income always reduces the marginal utility from work if diminishing marginal utility is true.

Conclusion

How big is this affect? Journalists favorable to a Basic Income tend to talk about "only" a 10% drop in labor supply. Let me make an invidious comparison.

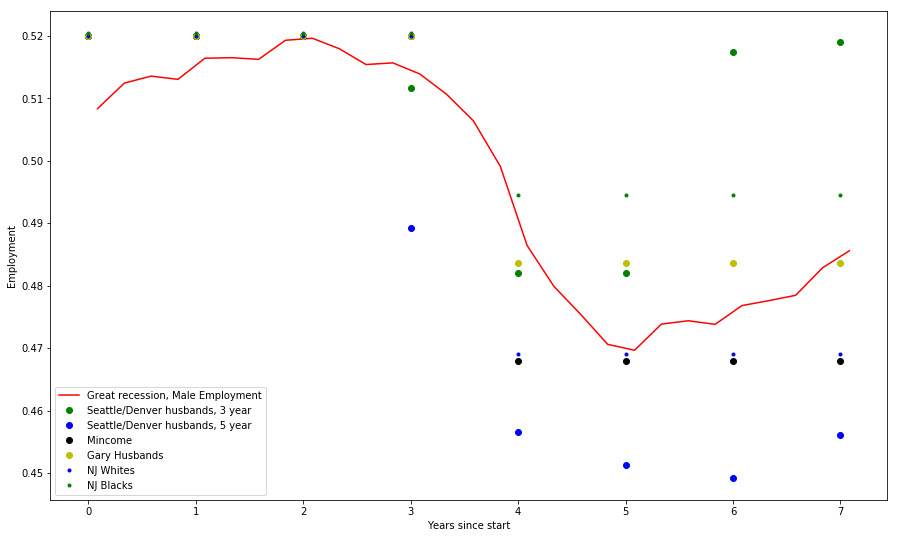

In 2008, the United States (and the world) suffered the Great Recession. To make a comparison, I've plotted the male employment to population ratio (approximated by taking the male civilian employment rate and dividing it by half of the US population) at the time of the great recession.

What would have happened if the Great Recession didn't occur, but we instead instituted a Basic Income in 2008?

To speculate about this, I assumed a baseline employment to population rate of 52% for men (the peak employment rate just before the recession). I then plotted for comparison the results of several Basic Income experiments focusing on the effects on men (though in a couple of cases that was not well disambiguated).

In the case of Seattle/Denver, I plotted the effect observed in each year. In the other cases, where yearly effects were not reported, I merely assumed a drop equal to the average reported drop.

The result can be seen above. The typical effects of a Basic Income are in the same ballpark as those of the Great Recession.

The conclusion we can draw from this is that all the available evidence suggests that a Basic Income will have a very large and negative effect on the economy.

We can also anticipate that the effect will be worse if people believe that a Basic Income is likely to be permanent. As can be seen by comparing the 3 and 5 year groups in the Seattle/Denver experiment, people assigned to a longer term BI reduced their work effort significantly more than those assigned to the short term BI.

Updates: Confirming the theory with out-of-time data!

Update 2020/3/5: Southern Ontario Experiment

(This section added to the blog post on 2020/3/5.)

As of 2019, I predicted that a Basic Income in North America would generally reduce labor supply by double digit amounts, approximately 10%. I now have out-of-time data that vindicates this prediction!

From 2017-2018, Southern Ontario ran a new Basic Income experiment. For what I believe to be political reasons, the pilot study was cancelled and the assessment was not performed using official government records. To make up for this lack of good data collection, some academics ran a poll on some of the people who were receiving Basic Income during the pilot. Due to this methodology - entirely self reported based on people's recollection of things from years ago - this study is far more speculative than the ones above.

However, the results are generally consistent with all the other studies. Of the BI recipients who were employed 6 months prior to receiving Basic Income, 23.9% report being unemployed during the Basic Income pilot. Of the people unemployed prior to BI, 81.8% remain unemployed. Changes in working hours were not measured.

This more recent study offers results in the same ballpark as all the older studies; Basic Income appears to reduce labor supply by double digit percentages. My prediction came true in out-of-time data!

Update: Barcelona

Barcelona ran a BI experiment in 2017 in which they gave a basic income to a set of low income residents. Labor market participation was measured via social security records, and includes point-in-time information at 10 day intervals on whether a participant was employed. A survey was performed at much less regular intervals to measure self-employment not captured by social security records, as well as measuring job search activity and civic engagement.

The net result is a 20% reduction in probability of being employed (from 47% to 37.5%) as per administrative records, and survey records suggest this effect is larger for full time employment.

Survey results also suggest no statistically significant increase in civic engagement, education or job search.

Update: Finland

Finland also ran a BI experiment. This is being widely touted by BI proponents as proving that BI doesn't reduce employment in wealthy countries, but the proponents seem to be ignoring the fact that it was given to unemployed people only. What the study does conclusively prove is that BI doesn't turn unemployed people into "double-unemployed" people who work a negative number of jobs. (Of course you don't need a study to prove that.)

Update on Keynesian Economics

A few commenters on reddit suggest that unemployment due to "low aggregate demand" is somehow different from reduced labor force participation due to Basic Income. However, this idea is based on either MMT or some weird newspaper columnist pop-Keynesianism; it is not in any way based on the economic mainstream.

Mainstream economist version of Keynesian theory says that in a recession, people do not work because they have sticky nominal wages but a shock has resulted in their real output dropping. Concretely, a worker has a nominal wage demand of \(W\) dollars. He used to produce \(K\) widgets at a cost of \(W/K\) each, but for whatever reason he can now only produce \(K_2 < K\) widgets. His real output is now \(K_2\) which has nominal value \(K_2 (W/K) = (K_2/K) W < W\).

In order to productively employ him the nominal wage must be reduced by a factor of \(K_2/K\). However, the worker refuses to work unless he is paid \(W\) dollars.

The Keynesian prescription of stimulating aggregate demand solves this problem by inflation; if the price of a single widget can be increased by a factor of \(K/K_2\), then the worker can again be paid a wage of \(W\) dollars.

In essense, stimulating aggregate demand is about tricking prideful workers into reducing their real wage demands so that they stop being lazy and go back to work.

In spite of the difference in mood affiliation, Keynesian economics claims that recessions reduce labor supply for the exact same reason a Basic Income does: workers refusing to work.

Appendix: Proof that Diminishing Marginal Utility implies a work disincentive from Basic Income

The choice to work can be framed as a question of utility maximization. Assuming one receives an income of \(I_w\) from work and an income of \(I_b\) from Basic Income, the utility of working is:

While the utility of not working is

Here \(U_w\) is the utility penalty that describes the unpleasantness of work. Let us define \(\Delta U_{bi}\) as the marginal utility gained by making the choice to work in a Basic Income regime:

In contrast, the marginal utility gained or lost from work in a non-Basic Income regime is:

The concavity relation (setting \(\alpha=I/(I_b+I_w)\)) tells us that for any \(0 \leq I \leq I_b+I_w\), we have:

Now if we compute the difference \(\Delta U_{bi} - \Delta U\), we discover:

If we substitute \(I=I_b\) and \(I=I_w\) into the concavity relation above, we discover:

Therefore:

This completes the proof that if Diminishing Marginal Utility is true, a Basic Income reduces the incentive to work.