Anyone following Nassim Taleb's dissembling on IQ lately has likely stumbled across an argument, originally created by Cosma Shalizi, which purports to show that the psychometric g is a statistical myth. But I realized that based on this argument, not only is psychometrics a deeply flawed science, but so is thermodynamics!

Let us examine pressure.

In particular, we will study a particular experiment in mechanical engineering. Consider a steel vessel impervious to air. This steel vessel has one or more pistons attached, each piston of a different area. For those having difficulty visualizing, a piston works like this:

The pipe at the top of the diagram is connected to the steel vessel full of gas, and the blue is a visualization of the gas expanding into the piston. The force can be determined by measuring the compression of the spring (red in the diagram) - more compression means more force.

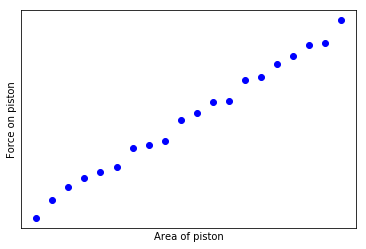

If we measure the force on the different pistons, we might makes a curious observation - the force on each piston is equal to a constant P times the area of the piston. If we make a graph of these measurements, it looks something like this:

We can repeat this experiment for different steel vessels, containing different quantities of gas, or perhaps using the same one and increasing the temperature. If we do so (and I did so in freshman physics class), we will discover that for each vessel we can make a similar graph. However, the graph of each vessel will have a different slope.

We can call the slope of these lines P, the pressure, which has units of force divided by area (newtons/meter^2).

To summarize, the case for P rests on a statistical technique, making a plot of force vs area and finding the slope of the line, which works solely on correlations between measurements. This technique can't tell us where the correlations came from; it always says that there is a general factor whenever there are only positive correlations. The appearance of P is a trivial reflection of that correlation structure. A clear example, known since 1871, shows that making a plot of force vs area and finding the slope of the line can give the appearance of a general factor when there are actually more than \(10^{23}\) completely independent and equally strong causes at work.

These purely methodological points don't, themselves, give reason to doubt the reality and importance of pressure, but do show that a certain line of argument is invalid and some supposed evidence is irrelevant. Since that's about the only case which anyone does advance for P, however, it is very hard for me to find any reason to believe in the importance of P, and many to reject it. These are all pretty elementary points, and the persistence of the debates, and in particular the fossilized invocation of ancient statistical methods, is really pretty damn depressing.

Particles explain pressure

If I take an arbitrary set of particles obeying Newtonian mechanics, and choose a sufficiently large number of them, then the apparent factor "Pressure" will typically explain the behavior of pistons. To support that statement, I want to show you some evidence from what happens with random, artificial patterns of particles, where we know where the data came from (my copy of Laundau-Lifshitz). So that you don't have to just take my word for this, I describe my procedure and link to a textbook on statistical mechancs where you can explore these arguments in detail.

Suppose that the gas inside the vessel is not a gas in the continuous sense having some intrinsic quantity pressure, but is actually a collection of a huge number of non-interacting particles obeying Newton's laws of motion. It can be shown that the vast majority of the time, provided the vessel has been at rest for a while, that the distribution of particle velocities is approximately the same in any particular cube of volume. Furthermore, the density of particle positions will be uniformly distributed throughout the vessel.

For simplicity, let us suppose the volume is cubic of length L, and one side of the volume is the piston. Consider now a single particle in the cube, moving with an x-velocity \(v_x\). This particle will cross the cube once every \(t=L/v_x\) units of time, and each time it hits the piston it will exert a force \(F=2mv_x\) every \(t\) units of time. Thus, on average the force will be \(F=2m v_x^2/L\).

The total force on the piston will be the sum of this quantity over all the particles in the vessel, namely \(F=2mN \bar{v}_x^2/L\). Here \(\bar{v}\) denotes the average velocity (in the x-direction) of a particle. If we divide this by area, we obtain \(F/A=2mN \bar{v}_x^2/L^3 = 2m \rho \bar{v}_x^2\). Here \(\rho = N/L^3\) is the density of particles per unit volume. I.e., we have derived that \(P=2m \rho \bar{v}_x^2\)!

Thus, we have determined that under these simple assumptions, pressure is nothing fundamental at all! Rather, pressure is merely a property derived from the number density and velocity of the individual atoms comprising the gas.

But - and I can hear people preparing this answer already - doesn't the fact that there are these correlations in forces on pistons mean that there must be a single common factor somewhere? To which question a definite and unambiguous answer can be given: No. It looks like there's one factor, but in reality all the real causes are about equal in importance and completely independent of one another.

(As a tangential note, several folks I've spoken about this article vaguely recollect that temperature is when the particles in a gas move faster. This is true; increasing temperature makes \(\bar{v}_x^2\) increase. If we note that \(\bar{v}_x^2 = C T\) - ignoring what the constant C is - and multiply our equation of pressure above by the volume of the vessel V, we obtain \(PV = \rho V 2m C T\). Since \(\rho V = N\), this becomes \(PV = N R T\), with \(R=2mC\). We have re-derived the fundamental gas law from high school chemistry from the kinetic theory of gases.)

Doing without P

The end result of the self-confirming circle of test construction is a peculiar beast. If we want to understand the mechanisms of how gases in a vessel work, how we can use it to power a locomotive, I cannot see how this helps at all.

Of course, if P was the only way of accounting for the phenomena observed in physical tests, then, despite all these problems, it would have some claim on us. But of course it isn't. My playing around with Boltzmann's kinetic theory of gases has taken, all told, about a day, and gotten me at least into back-of-the-envelope, Fermi-problem range.

All of this, of course, is completely compatible with P having some ability, when plugged into a linear regression, to predict things like the force on a piston or whether a boiler is likely to explode. I could even extend my model, allowing the particles in the gas to interact with one another, or allowing them to have shape (such as the cylindrical shape of a nitrogen molecule) and angular momentum which can also contain energy. By that point, however, I'd be doing something so obviously dumb that I'd be accused of unfair parody and arguing against caricatures and straw-men.

Shalizi is right, but only about a trivial philosophical point

I'll now stop paraphrasing Shalizi's article, and get to the point.

In physics, we call quantities like pressure and temperature mean field models, thermodynamic limits, and similar things. A large amount of the work in theoretical physics consists of deriving simple macroscale equations such as thermodynamics from microscopic fundamentals such as Newton's law of motion.

The argument made by Shalizi (and repeated by Taleb) is fundamentally the following. If a macroscopic quantity (like pressure) is actually generated by a statistical ensemble of microscopic quantities (like particle momenta), then it is a "statistical myth". Lets understand what "statistical myth" means.

The most important fact to note is that "statistical myth" does not mean that the quantity cannot be used for practical purposes. The vast majority of mechanical engineers, chemists, meteorologists and others can safely use the theory of pressure without ever worrying about the fact that air is actually made up of individual particles. (One major exception is mechanical engineers doing microfluidics, where the volumes are small enough that individual atoms become important.) If the theory of pressure says that your boiler may explode, your best bet is to move away from it.

Rather, "statistical myth" merely means that the macroscale quantity is not some intrinsic property of the gas but can instead be explained in terms of microscopic quantities. This is important to scientists and others doing fundamental research. Understanding how the macroscale is derived from the microscale is useful in predicting behaviors when the standard micro-to-macro assumptions fail (e.g., in our pressure example above, what happens when N is small).

As this applies to IQ, Shalizi and Taleb are mostly just saying, "the theory of g is wrong because the brain is made out of neurons, and neurons are made of atoms!" The latter claim is absolutely true. A neuron is made out of atoms and it's behavior can potentially be understood purely by modeling the individual atoms it's made out of. Similarly, the brain is made out of neurons, and it's behavior can potentially be predicted simply by modeling the neurons that comprise it.

It would surprise me greatly if any proponent of psychometrics disagrees.

One important prediction made by Shalizi's argument is that in fact, the psychometric g could very likely be an ensemble of a large number of independent factors; a high IQ person is a person who has lots of these factors and a low IQ person is one with few. Insofar as psychometric g has a genetic basis, it may very well be highly polygenic (i.e. the result of many independent genetic loci).

However, none of this eliminates the fact that the macroscale exists and the macroscale quantities are highly effective for making macroscale predictions. A high IQ population is more likely to graduate college and less likely to engage in crime. Shalizi's argument proves nothing at all about any of the highly contentious claims about IQ.